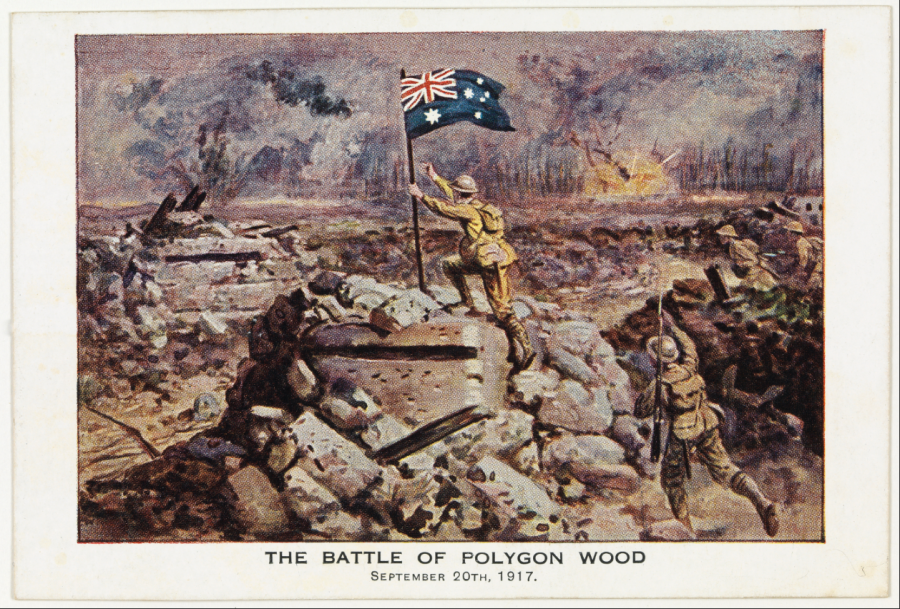

By this stage of the Ypres offensive, the wood had been “reduced to a moonscape of shell holes and tree stumps.”[2] The Germans sought shelter from the tremendous barrage in a series of concrete blockhouses (known as ‘pillboxes’ for their likeness to contemporary pill containers) that dotted the wood. Beyond the wood, to the north-east, the buttes of a pre-war Belgian army rifle range presented a major German strongpoint in that part of the enemy line.

Evidently restored from a four-month-long rest period, the 56th Battalion advanced across the broken battlefield eagerly and efficiently. Owing to their limited participation in the Battle of Messines, the men of 56th Battalion had little experience in pillbox fighting, but had received lessons from other British units who had. They knew that speed and aggression was essential. And so, despite their inexperience, the Diggers, as they had recently come to be known, quickly outflanked pillbox after pillbox. [3] As the Official War Correspondent and Historian Charles Bean recounted, “from some [pillboxes] came whimpering boys, holding out hands full of souvenirs”[4]. Elsewhere along the line however, the Germans did not surrender themselves so readily.

By mid-morning, the NSW-raised 14th Brigade, of which the 56th Battalion formed part, had secured its main objectives. Subsequent German counter-offenses were thwarted by the massed artillery. With few casualties and impressive gains, Polygon Wood was thenceforth in allied hands.

A SHOP ASSISTANT'S FIRST BATTLE

George Haskew was just 19 years old when he enlisted in the AIF in January 1916. Before embarking for overseas service, Haskew’s employer, Narrandera general store owner Robert Hankinson, gifted him an engraved wristwatch and presentation case. Wristwatches were not very common in 1916, and the generous gift was certainly a measure of the esteem in which the nineteen-year-old was held. In fact, the growing popularity of wristwatches was a by-product of the war; their practicality over the pocket watch quickly established in the trenches upon the Western Front.

On 6 September 1917, after months of training in Egypt and England, Haskew arrived in France. On 21 September, just days before the Battle of Polygon Wood, Haskew, then a corporal, was taken on the posted strength of 56th Battalion.

Fortunately, Haskew survived the battle completely unscathed. The same, however, cannot be said for his friend and uncle, Private Harold Spencer, with whom Haskew had enlisted.

A FATAL DETACHMENT

Despite embarking from Australia together, Spencer arrived in France almost a year before Haskew, arriving in Etaples on 11 September 1916. On 29 September, Spencer was taken on strength of 56th Battalion. He was first wounded in action on 2 April 1917, during the battalion’s advance towards the Hindenburg Line. Suffering a gunshot wound to the right thigh, Spencer spent months convalescing in England before returning to the front on 1 September 1917.

Unlike his nephew, Spencer did not remain with the 56th Battalion for the third battle of Ypres. Rather, on 16 September, he was detached for duty with the 1st Australian Tunneling Company. In preparation for the Battle of Menin Road—the battle which preceded that of Polygon Wood—the British Army sought to solve the “awkward problem” of moving forward several thousand troops “on to so small a front”[5]. For this, they decided to utilise every available shelter, including the German tunnel dug beneath the Menin Road. It was likely for the purpose of rendering the tunnel accessible for mass movement that Spencer was detached for duty.

In the days immediately following the battle, Spencer was maimed by multiple enemy shells. Although he was hastily admitted to the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance, he tragically succumbed to his wounds on 29 September 1917. He is buried in the Menin Road South Cemetery in Belgium.

Alas, for the Haskew family, Spencer’s death was not their first to grieve. Haskew’s older brother, Herbert, was killed in action during the Second Battle of Bullecourt in May 1917. Like his uncle, he too suffered the ripping violence of enemy shell fire.

Both Harold Spencer and Herbert Haskew’s memorial plaques, or ‘dead man’s pennies’, form the collection kindly donated the Anzac Memorial in 2020. Along with the men’s service medals and documents, George Haskew’s wristwatch and an album compiled of his wartime letters and postcards provide incredible insight into one family’s tumultuous experience of war and its aftermath.

ACQUITTED OF ALL CHARGES

Remarkably, for George Haskew, the unique strain of war did not coincide exclusively with his brief time in the frontline. In March 1919, Sergeant Haskew was court martialed for having ‘without reasonable excuse allowed to escape, persons committed to his charge whom it was his duty to guard.’ Presiding over the proceedings was none other than the ‘giant and genial’ Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Robert Cheeseman DSO, MC, commander of the 53th Australian Infantry Battalion, whose collection is on permanent display at the Anzac Memorial. Thankfully, witness statements attested that the escaped men were ‘notoriously bad characters’, and Haskew was acquitted of all charges. He returned to Australia in September 1919.

Despite surviving the war, Haskew would never forget his part in the Battle of Polygon Wood, nor the sacrifice of his friends and family in the pitiless campaigns of the Western Front. Both his sons, one of whom was named for his late brother, served in the Second World War.

Lest We Forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Charles Bean, in ‘Step-by-step: Polygon Wood’, Vol. IX, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edn., Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1941, p. 813.

[2] Brad Manera, In That Rich Earth, published by the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building, Hyde Park, Sydney, 2019, p. 89.

[3] During their extensive rest period, the men of I ANZAC keenly adopted the term ‘Digger’, previously reserved for New Zealand troops. The word spread quickly, and by the end of 1917, ‘Digger’ was the general term of address for Australian and New Zealand soldiers alike (Bean, 1941, p. 733).

[4] Charles Bean, in ‘Step-by-step: Polygon Wood’, Vol. IX, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edn., Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1941, p. 826.

[5] Charles Bean, in ‘Step-by-step: The Menin Road’, Vol. IX, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edn., Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1941, p. 747.