George Rayner Hoff was born on 27 November 1894 at Braddan on the Isle of Man, UK. Rayner Hoff’s father was a woodcarver and stonemason who restored old buildings. He later moved the family to Nottingham, where Rayner Hoff trained with his father while still at school. At 15 he began studying drawing, modelling, architecture and design at the Nottingham School of Art.

In 1915 Rayner Hoff enlisted in the army and arrived at Etaples in the Par-de-Calais area in northern France in December 1916. In 1917 he was transferred to the Royal Engineers topographical unit, where he spent the remainder of the war creating maps from aerial photographs. Read more on Rayner Hoff's war service. After the Armistice in November 1918 he spent a number of months with the British army in Cologne before moving to London to study sculpture under Francis Derwent Wood at the Royal College of Art; he returned to Nottingham in 1920 to marry artist Annis Mary Briggs.

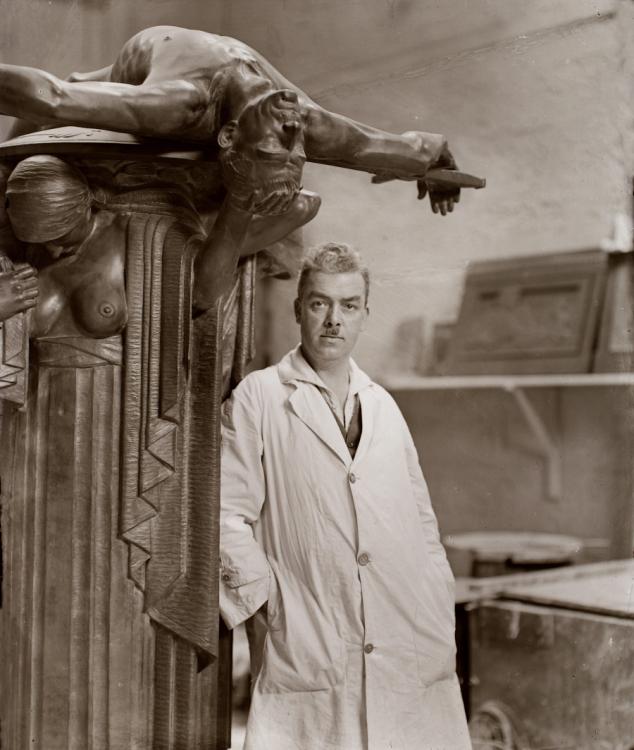

Rayner Hoff began exhibiting his sculptures in 1920, in 1921 he won first prize in sculpture at the Royal College of Art, the world's most influential postgraduate institution of art and design, and in 1922 received an Associateship of the Royal College of Art (ARCA). In 1923 he won the Prix de Rome, which funded three years in Italy and enabled him to further his classical training. After being recommended for a teaching post in Sydney, he left Rome after three months, and arrived in Australia in July 1923. He began work as head teacher of drawing, modelling and sculpture at East Sydney Technical College, Darlinghurst (later the National Art School), where he also established a private studio. Some commentators have suggested that his appointment was designed to assist with the anticipated demand for war memorials.

Once settled in Sydney, Rayner Hoff exerted an enormous influence on the development of Australian sculpture. He rearranged the courses at the college, ensuring that all subjects were supported by drawing. By the end of the decade, Rayner Hoff’s work at the college had produced a school of gifted sculptors and assistants. It was, according to Deborah Edwards, “perhaps the sole instance of a coherent school of production among sculptors in Australian history”. The sculpture produced there was “innovative, stylistically uniform and sexually adventurous”.

Hoff used the Art Deco style through the inter-war period to "modernise the past for the present". In doing so, he and his students expressed Australia’s postwar optimism and national fervour.

Hoff exhibited his own work annually at the Society of Artists and played a leading role on the executive of that association. In 1925 he completed reliefs for the Dubbo War Memorial, and in 1927 his Decorative Portrait – Len Lye won the Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Also that year, he was commissioned to design the sculptures on the National War Memorial, South Australia.

In 1930 architect Bruce Dellit commissioned Rayner Hoff to design the sculptures for the Anzac Memorial. He felt Hoff could supply the “dynamism” needed to complement the modernity of the construction.

Two years later, when the finished sculpture designs were exhibited in Sydney, the magazine Art in Australia devoted the whole of its October edition to Hoff. An article by Lionel Lindsay revealed that Hoff had significantly changed Dellit’s original concept for the monument’s central sculpture. Hoff designed a group of three female figures and a baby (representing mothers, sisters and wives and future generations), combined into a single column like a Greek caryatid; these mourning women supported a shield bearing a naked dead soldier.

The installation of external sculptures of members of the armed services and the medical corps was another major design change that emanated from Hoff. It was Dellit, however, who resolved to use cast granite rather than bronze for the figures on the buttresses, so that they would “appear as though growing forth from the stone surface”. This latter change emerged during the design phase.

Also exhibited in 1932 were the models for the two massive bronze sculptures by Hoff that were intended for placement in front of the east and west windows as substitutes for Dellit’s Peace Crowning Endurance and Courage and Victory after Sacrifice. These were Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914 and Victory after Sacrifice 1918, both of which featured naked women as the central figures. In the former, the female figure of peace was crucified on the sword and shield of Mars, above a pyramidal arrangement of dead and dying soldiers; the latter work depicted a victorious Australia under a representation of Britannia, also above a pyramid of lifeless bodies. The violent controversy that greeted the exhibition of these models prevented their development into full-size sculptures.

In Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914, Hoff employed his vitalist philosophy to show war “as a violent masculine attack” on the feminine force of “Peace/Civilisation”.

Had it been used, this sculpture would have introduced a strong anti-war message in place of Dellit’s more conventional image of endurance, courage and sacrifice. Similarly, in his Victory after Sacrifice 1918, the naked woman is positioned in a manner reminiscent of crucifixion.

Through these works, Hoff expressed his thoughts about the absolutely destructive nature of war overcoming the life force. Leading church figures found Hoff’s expression of these ideas blasphemous. One called Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914 “a travesty of redemption gravely offensive to ordinary Christian decency”; another found the use of a nude woman to represent civilisation insulting to “devoted wives, mothers and sisters” and thought that the crucifix itself was the most inappropriate symbol for the sculptures. Architect and designer Florence Taylor hated the brutal realism of the dead and dying figures at the bases of the sculptures and also thought “a nude, rude woman” totally unconnected with warfare and unsuitable for a soldiers’ memorial. Other artists seemed to be the only people willing to defend Hoff’s symbolism. The debate about the artist’s right to express his personal beliefs in a public memorial was only resolved to the satisfaction of the Establishment when these controversial sculptures were never built.

Winning the commission to create the numerous sculptures on the Anzac Memorial was the pinnacle of Hoff ‘s career. The task involved creation of 16 seated and four standing figures of servicemen and servicewomen in cast synthetic stone; four corner cast stone reliefs; and two long bronze bas reliefs over the eastern and western doors outside the building. Hoff’s contributions to the interior were, on the upper level in the Hall of Memory, the form of the 120,000 faceted gold stars that covered the domed ceiling; four relief panels showing the march of the dead each superimposed with symbolic representations of the armed forces; and the marble wreath surrounding the Well of Contemplation that framed the view of Sacrifice below. He and eight assistants in his studio were fully employed working on the Memorial between 1931 and 1934.

The vitalist–classical beliefs that embodied the male– female duality at the heart of life were at the centre of Hoff’s work. It was the sexual aspect of this duality that attracted the most intense criticism and prevented completion of two of the major sculptures Hoff designed for the Memorial. However, the ideas for these works came from his own experiences on the Western Front. They were as he explained, “designed in a spirit of reverence for those who made the sacrifices demanded by war, yet to avoid glorifying war lest we forget its folly”.

Because of his belief that male–female sexuality created the human life force, and that male and female were equally important to society, Hoff gave considerable prominence to female contributors to the war effort and to the women who had lost their fathers, husbands or sons. Nurses were prominent among the figures representing the services, and women were central to the group sculpture Sacrifice. In contrast to his earlier work Idyll: Love and Life which celebrates the living unity of man woman and child, Sacrifice shows the separation of the dead from the living. Rather than being aligned with the women who support him, the dead young soldier is separated from them by the shield and sword that represent war; his body lies across them in a horizontal line that ends the vertical strength of the female support. In 1932 Hoff explained the prominent position of women in this work:

… In this spirit I have shown them carrying their load, the sacrifice of their menfolk.

Hoff became Lecturer-in-Charge of East Sydney Technical College’s Art Department from 1933 until his death in 1937. Hoff’s other public sculptures in Sydney included a large bas relief Theatre Arts placed in the foyer of Dellit’s Art Deco Liberty Theatre (the theatre closed on 30 January 1975); a bas relief of Mercury in Transport House, York Street; and several sculptures in Emil Sodersten’s City Mutual Life Building in Hunter Street.

However, in spite of his obvious success, Rayner Hoff was unable to shake the controversy surrounding works such as Sacrifice, Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914 and Victory after Sacrifice 1918. In addition to the disapproval of Catholic Archbishop Kelly, these works drew censure from the Master Builders’ Association of New South Wales and the local chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. His design for the Victorian centenary medal was also criticised. The stress of these encounters, his workload at the art school and new commission for work, damaged his health and he died of pancreatitis at the age of 42 on 19 November 1937.