Ten days after his 21st birthday George Rayner Hoff registered his intention to enlist and follow his brother Thomas into the Army Cycling Corps. He was attested into the Army Reserve and given the registration number 383.

Britain's war establishment in the months that followed the outbreak of hostilities could not cope. The rush to enlist at the outbreak of war had caused a massive expansion from a tiny professional service based on locally raised regiments to a huge volunteer army. It needed materiel, food, training facilities, equipment, instructors, administrators, officers and non-commissioned officers (NCO). They did not even have enough socks and underwear.

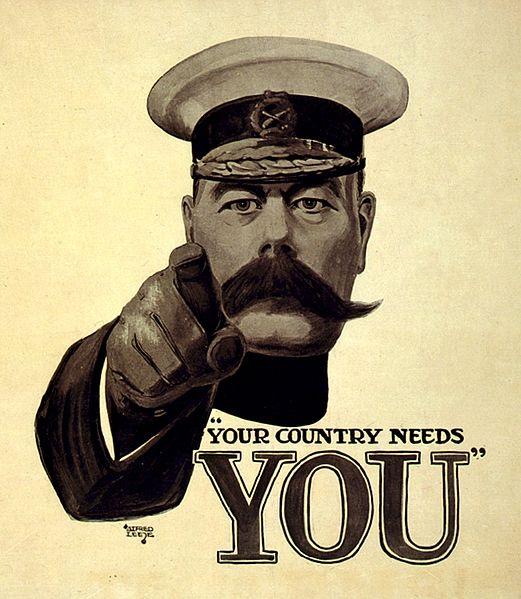

General Kitchener, the legendary liberator of Khartoum, conducted a monumental recruiting drive demanding ‘Britain needs you’ apparently without considering the ability of the British Army’s attestation and induction infrastructure to deal with the influx. People flocked to join up but the old county regiment system could not cope. The backbone of the pre-war British Army was the collection of county regiments. In the 19th century and through to the end of the Edwardian period a typical British county regiment might have two battalions with about 800 men in each. The enthusiasm to enlist in Kitchener’s New Army caused each of these regiments to blow out to dozens of battalions, each 1,000 men strong. The new officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were drawn from community leaders or nominated from amongst the ranks. Few had any prior military training. Almost none had any combat experience. Even the experienced commanders had little concept of what a 20th-century war might mean. One such example was General Horace Smith Dorian. His first field command had been against the Zulus at the battle of Isandlwana. In 1914 he was commanding a modern mobile army on the Belgian frontier.

FROM ENLISTMENT TO WAR

When George Rayner Hoff attempted to enlist as a Private in the North Midland Division's Cycling Corps he told them he was 21 years and 1 month old and a sculptor by profession. He entered his faith as ‘Church of England’ and stated that he was not married. He gave his name as George R Hoff and listed his mother, Elizabeth Amy Hoff, of Cloister Cottage, Nottingham, as his next of kin. On initial examination his height was recorded at 5’ 6¾” and chest measurement of 36” when fully expanded. Hoff was graded ‘A1’ and the inspecting medical officer even noted that he had a small scar on the back of his right hand and ‘good teeth’. On 8 December 1915 Private George Rayner Hoff was accepted into the British Army Reserve.

As casualties mounted and the training camps sent their graduates off to the war there was room at last for Hoff to report for full-time service. Four days after the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force landed on the beaches of Gallipoli George Rayner Hoff became Private (Pte) G R Hoff with the regimental number 15664. By this time the infantry needed men and Hoff's intention of enlisting in the Cycling Corps with his brother Thomas was ignored. In 1916 Hoff was given a new army number 57714 and posted to the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regiment. The third Hoff brother, Sidney, would serve in the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire (Notts & Derby) Regiment.

Until late 1915 training in the Kings Liverpool Regiment, as in any other county regiment in the British Army, was conducted in much the way it had done in the wars against the Romanov Army in Crimea in the 1850s and little different to the training received by the British Army that fought Napoleon a century earlier. The only real addition to the spirit of the bayonet was an encouragement of attaining skill in sustained rifle fire with their brand-new weapon the Short, Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE), .303” calibre, bolt action service rifle. There was little appreciation of the talents that individuals were bringing to the ranks of this volunteer army drawn democratically from across Britain and inspired by patriotism and duty.

Training consisted of a basic introduction to the life of a soldier that taught a man how to lace his heavy, ankle-length, leather and hob nail ‘ammunition’ boots, wind his 9” (almost 3m) long woollen puttees and assemble the complex tangle of straps and bags that made up his 1908 pattern webbing equipment or, for the New Army, the 1914 pattern leather equipment.

The recruit had to be taught that three five round clips of ammunition are stored in 10 small pouches on the front of the belt, rations and eating kit he stuffed into the haversack on his left hip with his bayonet while an enamel water bottle sat uncomfortably on his right and a spade head hung in a bag behind. On his chest beneath his chin he wore a bag containing his gas mask in what the Army called the ‘ready’ position. In marching order he buckled a heavy pack loaded with blanket, overcoat, helmet and other necessaries to his back. The soldier learnt how to use his rifle, without shooting himself or his mates, and how to stand still at attention or march in step with the hundreds of equally inexperienced novices around him.

These new soldiers had to develop a knowledge of tactics. They had to learn and understand the relationship between sub-units like the section of 12 men he belonged to, within the platoon of 40 men, within the company of 200 men, within the battalion of 1,000 men that was his unit. They had to know where their unit fitted within the brigade of 4,000 men within the division of 15,000 men within the corps of 30,000 men within the army of 100,000 men or more.

Pte Hoff the soldier had to acquire knowledge that Rayner Hoff the artist would never even have considered. He had to understand how an infantryman related to an artilleryman or a signaller or a medic or an engineer or a transport driver of the Army Service Corps or any of the thousands of other jobs and military skills an army requires of its soldiers.

We can only wonder at how an artistic temperament dealt with military hierarchy, routines and orders. Hoff would have had to learn his place and how it related to his corporal section commander, with his platoon sergeant and the officer, a lieutenant, who led his platoon. He learnt that his company was commanded by captain or a major and that his battalion was commanded by a lieutenant-colonel. His brigade was initially commanded by a full colonel and later a brigadier general and so on as the formations got larger up to the generals and field marshals that Pte Hoff was never likely to meet.

This was all of the arcane knowledge that a private soldier needed to assimilate before he could go on to battalion training and learn how all of the sub-units of a coordinated body of 1,000 soldiers needed to function as a single body and think with a single mind. He had to acquire the basic skills of marksmanship, field craft, first aid, and learn to beware of military crimes that could earn him field punishment or worse.

After 20 weeks of this the British Army considered Pte Hoff ready for war, or at least at the end of his basic and battalion training.

The scant surviving records maintained by the British Army during the First World War indicate that Hoff applied himself to his new role. The only misdemeanour on his service record occurred at the end of his basic training when he decided to award himself an unofficial 24-hour leave pass for his 22nd birthday. Pte Hoff went missing on the afternoon of 26 November 1916, spent his birthday absent without leave, and turned himself in at 3pm the following day. Hoff must have been reasonably popular with his officers as the punishment he received for this offence was, by the British Army standards of the time, relatively light. He forfeited two days’ pay and spent six days confined to barracks.

With the initial phase of his training complete and all of his equipment and necessaries bought up to date Pte Hoff and his draft of reinforcements were shipped to France on 11 December 1916 to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

On arrival in France Hoff was sent to No. 24 Infantry Base Depot at Etaples in the Par-de-Calais area of northern France.

Etaples had the reputation for being one of the toughest training camps created by the British Army during the First World War. Its main parade ground was nicknamed ‘The Bullring’. The facilities were primitive and the drill instructors were notorious for their brutality and savagery. The camp suffered the biggest mutiny in the BEF during the First World War and its military prison was the site of several executions. In the harsh winter of 1916–17 it must have been a truly miserable place. Fortunately for Pte Hoff he was only there a week before joining his Battalion where it was stationed in reserve behind the front in Picardie.

THE WESTERN FRONT

At the time that Pte Hoff joined his Battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regiment the Wetern Front stretched in a jagged line from the Swiss frontier all the way to the North Sea. The British sector was in the north, from the Somme Valley across France and into that little piece of Belgium around Ypres (Ieper) that remained resisting German invasion.

Although the opposing armies faced each other on either side of no man's land from zigzag lines of trenches the front and its supporting area on both sides could be 10 to 20 kilometres deep.

By the time Hoff got to the Western Front no man's land ran into an area of the combat zone dominated by outposts. These outposts could be concrete blockhouses with machine gun nests nearby or sandbagged positions sited for all-round defence and located to break up an enemy attack on the front line. Beyond the belt of outposts was the front line. The front line comprised fighting trenches protected by barbed wire. These fighting trenches connected shelters, firing bays, listening posts and machine-gun positions. There were several lines of fighting trenches in depth (behind the most forward trench). Secondary fighting trenches had dugouts for platoon and company commanders as well as first aid posts and nooks hewn into the trench walls in which the soldiers could snatch a few hours of sleep.

These fighting trenches were connected to support trenches by communication trenches that branched at right angles. Communication trenches were usually dug wider and straighter than the fighting trenches to allow carriers to take ammunition and food forward to the fighting trenches and bring the wounded back.

The support trenches, behind the fighting trenches, were occupied by the battalion or brigade reserves and included battalion commander’s dugouts. Signallers, tunnellers and other engineer and support troops operated from these trenches and wounded soldiers could find slightly better and more comprehensive medical treatment in the aid posts that sheltered in them.

Within the complex of support trenches there were deeper and more established dugouts for accommodation, communication network hubs, formation headquarters and forming up positions for battalions going forward into the front lines or preparing for an attack.

Within or behind the forward support trenches were field artillery positions, field kitchens, supply dumps and headquarters for the command and control of more senior formations. The furthest of the support trenches were usually beyond the range of field artillery but still subject to barrages by long-range guns.

Even further from the front were rear areas where there were divisional headquarters, field hospitals, communications networks, heavy artillery batteries. Behind the trenches the soldiers would encounter massive supply dumps, transit camps for men, stables for horses, service facilities for motorised transport and tanks.

Further behind the lines were military schools, barracks, headquarters where Generals and Field Marshals planned battles, rest camps where troops could get fresh food and sleep in clean sheets, even visit an estaminet, hold sports days and otherwise rebuild themselves to go back into the fighting trenches

There were airfields for the new biplanes that were taking the war to the skies, of convalescent hospitals and laboratories that could develop photographs and printing presses that could publish instruction manuals for replacements to learn from print what the veterans had picked up the hard way - if they survived. These substantial areas of France and Belgium from the front lines to the rear areas were under military administration, a little military republic run by the French, British or Belgium armies on one side and the German Army on the other, remote from control by civilian law.

Beyond the areas administered by the military there were the French provincial towns, barely touched by the war, where men could take leave, where existing infrastructure could provide bases for essential non-combatant tasks to maintain the British Expeditionary Force and equip it to communicate with its French and Belgian and Portuguese and Italian allies

This maze landscape from the front line to the rear echelon had developed since the German invasion that had almost reached Paris in 1914. The countryside was fought over through the battles of 1915 and the great offensives of 1916. As a result this zone, tens of kilometres wide and hundreds of kilometres long, was crisscrossed with existing roads and newly created highways, railway networks and foot and vehicle tracks.

Closer to the front those paths were obliterated or further confused by the shell shattered terrain. All of this was spread out across the rolling countryside that initially looked flat and featureless but, on closer examination, its gentle undulations gave a deceptively close horizon.

During the winter of 1916–17 Pte Hoff's Battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regiment was in a reserve position on the Somme. It was cold and wet and muddy. The Battalion was put to tasks like road and trench maintenance. They built shelters that others, in transit between the fighting trenches and the rear, could use. They gathered timbers that roofed their shelters and burned in their braziers.

HOW THE WAR HAD CHANGED

In 1914 the First World War had been one of movement. Mass armies swept across the north European plain. In 1915 the fighting bogged down. Fighting soldiers on both sides dug into the earth to protect themselves from the new, high velocity, rapid fire weapons. As the year wore on the excavated strong points linked up or grew into each other to become lines of opposing trenches.

By early 1916 the French Army had done most of the fighting and most of the dying on the Western Front in Europe. The British Government had been searching for side show campaigns elsewhere that would create a miracle breakthrough and end the war with minimal economic and social cost. Instead they lost a campaign at Gallipoli and an army in Mesopotamia.

On 1 July 1916, under growing pressure from the French, the BEF launched its first major offensive on the Western Front. On the first day of that offensive they lost 60,000 men killed or wounded on the northern banks of the Somme River Valley. The slaughter went on until it bogged down in the November mud. The ground captured could be measured in hundreds of yards while the dead could be counted in hundreds of thousands.

On the Somme the BEF High Command was suddenly and brutally made aware that it had to learn how to fight a 20th century war. They needed to coordinate arms and men and materiel. They needed to be able to communicate and to provide effective and timely logistic supply. They needed to take advantage of new technologies.

Back in the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regiment Pte Hoff had impressed his superiors.

He was obviously energetic and had literacy and artistic skills. In the new war a man like Hoff could do more damage with a pen and protractor than with a rifle and bayonet. He was posted to a developing branch of the British service – the Field Survey Companies – created within the Corps of Royal Engineers.

On 7 January 1917 Pte George Hoff was seconded from his battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regiment to No. 3 Field Survey Company RE, one of the specialist units tasked with gathering and collating the data from aerial photographs and infantry patrols and turning them into modern usable military topographical maps.

HOW HOFF'S WAR HAD CHANGED

We've delved a little into the the complex nature of the war on the Western Front. Ask yourselves how did a bag of spuds or a barrel of salt pork get from a commissary store in Portsmouth to where it was needed with the men in the front line near Bullecourt?. How did a limber full of 18 pounder field gun shells get from the Woolwich Arsenal to where the artillery crews could feed their guns on the ridge at Pozieres? Even if stores and men could get to France how did they find their way to where they were needed? How could long-range gunners predict what was on the other side of the hill and effectively register shells to land on the concealed batteries that were slaughtering their infantry? The BEF needed to know exactly where its own position was, where the enemy was and the general rise and fall of the ground between the two positions. They needed survey. They needed maps The best the French could provide were 1:80,000 scale maps of varying accuracy and with no contours. This was not good enough. The BEF needed to find, hone skills and train map makers. Failure to do so was not an option. The first Field Survey companies were formed in France in March 1916. In July they came under the organisational wing of the Royal Engineers (RE). In February 1917, as Pte Hoff was settling in to his new posting, the Field Survey Companies were given a fixed establishment comprising a headquarters, topographical section, map section, observation section and sound-ranging section. This was the small band of specialists that Pte George Rayner Hoff had joined. Within three months Pte Hoff had made a significant contribution to his new and experimental unit. The Field Survey Companies were demonstrating their value and his unit commander wanted Pte Hoff on his team. He was transferred to the Royal Engineers. In one of the few known pictures of Hoff in uniform during the war he is photographed wearing the service dress of a Sapper in the Royal Engineers. With his official transfer into the RE he was given the army number 244735 and the rank of Sapper (Spr). Spr Hoff and his men worked with the existing maps. Some of them operated in the field with plain tables, theodolites and compasses. Others interpreted aerial photographs.

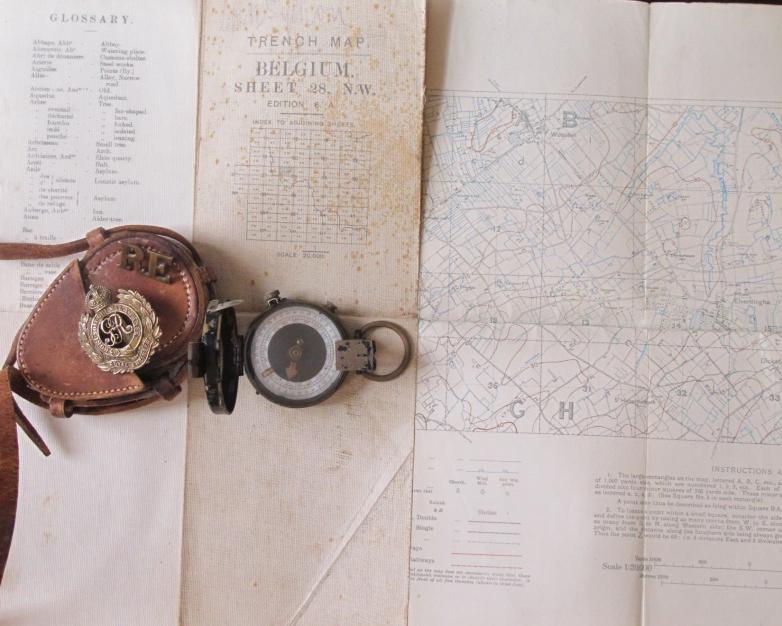

Spr Hoff's drafting skills equipped him to bring all this information together and make finer and finer maps. Just as the Somme offensive was about to be launched the first of the Field Survey Company Engineers produced a 1:20,000 scale map. These were rare but vital. They revolutionised the artillery and infantry war on the Western Front. By the time Hoff joined No.3 Field Survey Company 1:20,000 was the standard.

As a draughtsman he collated all of the information provided by his mates in the field and turned them into trench maps that were the envy of every army in the Great War. Craftsmen like Spr Hoff turned their work over to the publishers who churned out these maps in their tens of thousands. At the beginning of the war generals had maps. By 1917 the most junior lieutenant in his early 20s had one in his tunic pocket and usually a second to pass on to his platoon sergeant.

Spr Hoff stayed at his drawing board through 1917 and the disastrous battles for the Passchendaele ridgeline above the Ypres Salient in Belgium. At the end of the battle of Passchendaele Spr Hoff received further recognition for his skills by having his military trade rating increased to that of ‘Superior Draughtsman (Topographical) – Skilled’. It didn't mean promotion but it did see an increase in his pay.

1918: YEAR OF VICTORY

In March 1918 the Germans launched their massive spring offensive on the Western Front. The BEF was forced to retreat almost as far as the positions they had held in the disastrous days of 1914.

The change in the front and a war of movement meant the need for more maps quickly.

Spr Hoff was sent to the Depot Field Survey Company for a week. He may have been instructing new intakes of draughtsman cartographers or undertaken a short course of instruction himself but on 6 April 1918 he re-joined his Field Survey Company from the Depot Company.

At the end of the month the German offensive had been fought to a standstill. The war of movement and outmanoeuvre had ended in Britain's favour and much of that was due to the quality of their maps.

In May 1918 the Field Survey Companies were reorganised into Field Survey Battalions. The British and French were preparing to launch their own offensive. A British Field Survey Battalion comprised headquarters - including survey printing sections, two artillery sections, incorporating the sound ranging and observation sections, and a corps topographical section.

There was one Field Survey Battalion for each of the five British Armies. For tactical purposes they were placed under the General Officer Commanding Royal Artillery in each army. The Field Survey Battalion in which Spr George Rayner Hoff was serving was part of Sir Julian Byng’s 3rd Army.

By the summer of 1918 the balance of power on the Western Front had swung in favour of Britain and France and their allies. US troops were arriving in massive numbers. The new weapons, like powerful and effective tanks and specialist fighter, bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, could be counted in their hundreds. Transport, artillery and communication was faster and more effective than it has ever been.

The allies were ready to go on the offensive. On 8 August an irresistible tide of tens of thousands of British, Canadian and Australian troops, led by tanks and aircraft and supported by massive artillery barrages, swept over the thinly held German positions beside the Somme Valley. The German Army was thrown into headlong retreat. They fell back on the Siegfried Line (referred to by the British as the Hindenburg Line) but even this could not stop the allies. After 100 days of bloody fighting, facing defeat in the field and revolution at home the Imperial German Army’s High Command surrendered.

At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918 the guns fell silent on the Western Front. Spr Hoff would turn 24 a fortnight later. In December he was granted 14 days leave to Britain, He could have Christmas and the New Year with his family.

In January 1919 Spr Hoff returned to France. Peace had settled on a devastated landscape that demanded almost as many maps the fighting had. The Army still needed the skills of men like Spr Hoff. For the time being he would have stay in uniform and in France.

AFTER THE ARMISTICE

Sapper George Rayner Hoff had not arrived in France and been sent to the Front until the end of 1916. He had received no decorations or war wounds. He did not have dependents desperately awaiting his return. As a result his repatriation and discharge was given a low priority. The combat veterans of the early battles of 1914 and ‘15 were repatriated first and on top of this his specialist skills were still useful. Despite the Armistice he would have to serve on.

When Spr Hoff returned to France from home leave in early 1919 he was transferred to the 4th Field Survey Battalion, part of the Royal Engineer component of the British Occupation Army that was to deploy to post-war Germany on garrison duty.

In Germany he found none of the devastation that had been suffered in France or Belgium. Spr Hoff and the other Royal Engineers were based in Cologne. We can only imagine what the young artist must have made of this mediaeval city untouched by the ravages of war.

As a survey engineer in the British Occupation Army Sapper Hoff’s days were unlikely to have been busy. He could have taken advantage of sightseeing and explored the ancient city.

With the war over leave was more plentiful. On 28 June 1919 Hoff was given another 14 days leave to Britain so he could share a little of the summer with his family.

By mid-July Spr Hoff was back in Germany and spent the rest of the summer and early autumn studying the countryside. On 13 September 1919 he was finally told to pack up and go home

In October 1919 244735 Sapper George Rayner Hoff was demobilised and discharged. Spr G R Hoff the warrior could be George Rayner Hoff the sculptor once again.

Article by Brad Manera