Among the British troops at Inkerman were 600 British sailors, men of the Royal Naval Brigade. Their task was to serve the massive 68-pounder Lancaster guns that fired from the heights into the city of Sebastopol. As the Russians surged up the ravines, the sailors fought alongside the soldiers to save their guns.

At a battery on Victoria Ridge, Seamen Thomas Geoghegan, who had just returned from being treated for wounds he had received at Sebastopol, James Gorman, the short (5’2” or 157.5cm), wiry 20 year old, and his shipmates from HMS Albion, Thomas Reeves, Mark Scholefield and John Woods, climbed onto the low parapet erected to protect their guns. Around them fellow sailors and British infantrymen lay dead or dying. From their vantage point, the five sailors of the Naval Brigade could see, down through the thinning fog, elements of a regiment from Lieutenant-General Soimonoff’s 10th Division forming to attack them from Careenage Ravine.

What chance would five men, armed with single shot rifles, have to stem a charge? The sailors prepared to sell their lives dearly and fired a thin volley into the advancing Russians. Sheltering behind the parapet, the wounded British soldiers gathered the discarded rifles and muskets from the bodies around them. They loaded and capped the weapons and handed them up to the sailors, allowing them to deliver a rapid fire that shocked the enemy.

As rank after rank approached the sandbag wall along a narrow re-entrant, they were cut down. Time and again the Russians attacked. Geoghegan and Woods were killed. Gorman, Reeves and Scholefield kept up the fire. The exhausted Russians retreated.

Blackened by power smoke, ragged and grazed by near misses and bruised by the recoil of their weapons the three could finally stand down. Each would be awarded the Victoria Cross.

In the words of the collective recommendation:

‘Thomas Reeves, Seaman, James Gorman, Seaman and Mark Scholefield, Seaman. At the Battle of Inkermann, 5 November 1854, when the Right Lancaster Battery was attacked, these three seamen mounted the Banquette, and under a heavy fire made use of the disabled soldiers’ muskets, which were loaded for them by others under the parapet. They are the survivors of five who performed the above action. (Letter from Sir S. Lushington, 7th June, 1856.)[1]

When asked by William Howard Russell, the Crimean War correspondent for The Times, why they had defended the guns and the surviving casualties, one of the sailors replied that “They wouldn't trust any Ivan getting within bayonet range of the wounded.”[2]

In an age before posthumous decorations, Seamen Geoghegan and Woods would remain unrecognised.

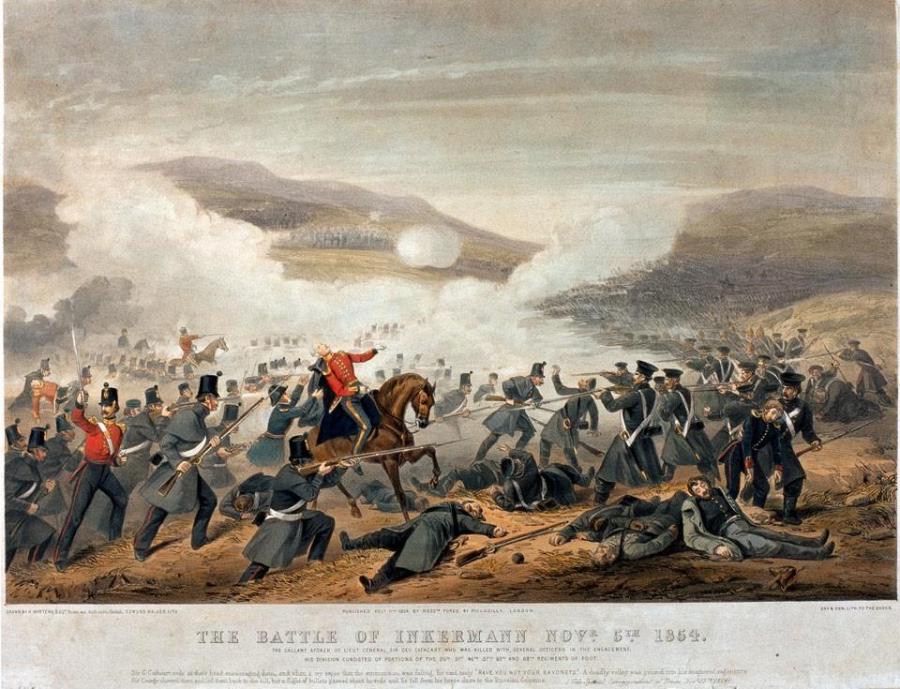

After hours of bloody assaults, the Russians finally retired from the field of Inkerman, leaving over a third of their number dead or wounded on the battlefield. The British and French suffered approximately 3,300 casualties.

For Seaman James Gorman and the others, there was no rest. They advanced to siege lines during the dreadful winter of 1854. The conditions brought on rheumatism, but young Gorman endured. In one of the clashes his commander, Captain Stephen Lushington RN, was unhorsed and surrounded by the enemy. Gorman, though badly wounded, fought his way through to the officer, drove off the Russians and affected a rescue.

The severity of his wounds had Gorman shifted to the infirmary on his ship where he served out the rest of the war, returning to Britain in January 1856. In Britain he was returned to hospital until discharged at the end of May. He suffered civilian life for less than a fortnight before reenlisting.

Serving aboard HMS Elk, Able Seaman James Gorman VC found himself bound for another war, the Second Anglo-Chinese (or Opium) War. He fought in the battles at Fatshan Creek in May/June 1857 in which dozens of Chinese war junks were captured or sunk and a Chinese coastal defence fort taken. He was with the Naval Brigade at the capture of Canton in the week around New Year 1858. By the end of the war, James Gorman had been promoted petty officer.

He was still aboard Elk when she sailed for the Royal Navy’s Australia Station, docking in Sydney on New Year’s Eve 1858.

Petty Officer James Gorman VC served over two years in Royal Naval vessels protecting the colonies of NSW and Victoria. He returned to Britain for discharge in late 1860 but the antipodes lured him back.

By then a former sailor, James Gorman arrived in Sydney aboard the Fairlie on 29 April 1863 as an assisted immigrant. He soon found work as a sailmaker and resided in Kent Street, later moving to Sussex Street. On 10 November 1864 he married Mary Anne Jackson at St Phillip’s Church and the following year their only child, Annie Elizabeth, was born.[3]

In May 1867 Gorman joined the staff of the Nautical Ship School Vernon which was moored off Woolloomooloo at Farm Cove, near Mrs Macquarie’s Point. The ship was moved to the north-eastern corner of Cockatoo Island (or Biloela as it was sometimes known) late in 1870 where an industrial school for girls was located in old convict buildings at the top of the island. With his long naval experience and his gallant decoration, he was highly competent for the position and he was placed third in charge.

The Vernon had been inaugurated as a nautical ship school in April 1867. It was a floating home to some of Sydney’s neglected, abandoned, orphaned and delinquent boys who were in danger of a life of pilfering, petty crime and frequent stints inside Darlinghurst Gaol. The ship had room to accommodate 264 boy denizens aged from 5 to 16 years of age and it provided basic schooling. The boys were also taught seamanship and useful industrial skills such as carpentry and shoemaking before being apprenticed out to tradesmen and farmers until they turned 18. On the Vernon, they were constantly supervised by a full crew of experienced sailors and well-chosen school-masters. Gorman seems to have used his impeccable military reputation with the wayward boys when it came to disciplinary matters. According to one of his colleagues,

‘He visited punishment on the boys promptly and was always among them. He was a terror to the bad boys, and the good boys regarded him with affection, and would not do anything to displease him. In fact, he only had to speak, and all was peace and quietness.’[4]

Gorman worked on the Vernon for fourteen years and was ‘greatly esteemed for his sterling good qualities both by officers and boys.’[5] In June 1881 he was appointed Foreman of Magazines of the Ordinance Department at Spectacle Island, the oldest naval stores complex in Australia. His new position carried a salary of £175 a year. Just over a year later, on 18 October 1882, Gorman died suddenly following a catastrophic stroke. He was forty-seven years old. The hapless hero was buried in the Balmain Cemetery on 20 October. Among the many mourners were the officers stationed at Spectacle Island and a strong detachment of boys from the Vernon who formed the firing party to give the usual naval salute. On the following day the Sydney Morning Herald printed a very generous obituary to the VC winner, headed ‘Death of a Naval Veteran.’[6]

Balmain Cemetery (which was situated off Norton Street in Leichhardt) was levelled in 1944 to create Pioneers Memorial Park. The park was to be maintained by the council as a tranquil rest area and picturesque garden dedicated to the original pioneers of the district. Sadly, most of the headstones from the cemetery, including Gorman’s, were removed and destroyed. Today, James Gorman and his final resting place are however acknowledged on a plaque on the tall and elegant memorial in the park which was erected in remembrance of the men from Leichhardt who fell during the Great War. The memorial originally stood in the grounds of Leichhardt Town Hall and it was unveiled by Sir Walter Davidson, Governor of New South Wales on 9 April 1922. It was moved to its present site when the park opened in November 1944. The simple yet significant plaque inscribed ‘James Gorman, V.C. 5-11-1854 Battle of Inkerman’ was probably added at this time.

On November 11 2001, another small plaque in memory of Seaman James Gorman VC was attached to the Balmain War Memorial in Loyalty Square Balmain.

We can only wonder what James Gorman VC would have made of the loss of his headstone and gravesite. I think that having survived the horrors of Inkerman, Sebastopol and Canton, then growing into the nurturing master of wayward boys, may have made him very philosophical. There is no evidence that he objected to another sailor in the Royal Navy, with the same name, claiming the supplementary pay that goes with the award of the Victoria Cross, that James was entitled to, for two years. The other, Ordinary Seaman James Gorman of HMS Woodcock, was eventually discovered, fined and imprisoned in Hong Kong before being discharged in disgrace in 1859. Nor did it appear to upset Gorman, or perhaps he never discovered, that another, James Devereux of Southwark in London, claimed that he was James Gorman VC, Royal Naval hero of the Battle of Inkerman. Devereux died penniless in 1889.

In my mind’s eye I can see the dignified old sailor shaking his head in amazement at the news that his medals sold in October 2020 at Dix Noonan Webb in London for £240,000 plus premium and auction fees.

I hope that you spare a thought for veterans like James Gorman VC next time you see a street, a suburb or a town that preserves the name of a lost battlefield or a forgotten hero.

Article by Brad Manera and Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

*Museum quality replica VC made by Hancock’s Jewelers, London. Courtesy of Brad Manera Collection. Photograph by Stephanie Bailey.

**Chamberlain, WHJ & AWF Taylerson, Revolvers of the British Services 1854-1954, Museum Restoration Service, Ontario, 1989, p 2.

***During the Crimean War both sides were issued with muzzle-loading, percussion cap firearms. Some British units still had the relatively short-range smoothbore, calibre .75”, Pattern 1842 Musket while others had the innovative .702” Pattern 1851 Minié Rifle. As production increased supplies of the new and powerful .577” Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle became available.

[1] V.C. Citations, London Gazette, 24 February 1857.

[2] Russell, William Howard The British Expedition to the Crimea Book 1, London, 1859.

[3] Anthony Staunton & Harry Willey, ‘James Gorman VC Remembered at Leichhardt’, Leichhardt Historical Journal No 16, June, 1989, p 5.

[4] Cited in Sarah Luke, Like a Wicked Noah’s Ark; The Nautical Ship Schools Vernon and Sobraon, Arcadia, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, p 10.

[5] ‘Death of a Naval Veteran’, Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 21 October 1882, p 9.

[6] ‘Death of a Naval Veteran’, Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 21 October 1882, p 9.