Western Timor became part of Indonesia when the Dutch formally withdrew in 1949. The Portuguese, however, retained ownership of eastern Timor until 1975. When the Portuguese finally decolonised, the people of East Timor got a brief taste of freedom. Tragically, that dream of self-determination was crushed when the Indonesian army invaded shortly thereafter.

To organise and conduct an anonymous ballot, the United Nations Mission East Timor, or UNAMET, was established[1]. The referendum, which occurred in August 1999, produced an overwhelming ‘yes’ vote. Consequently, pro-Indonesian militia—sometimes backed by Indonesian police and military forces—unleashed a devastating campaign of murder, arson and terror. Countless civilians were killed, and more than 500,000 displaced[2].

In response, the Australian government established INTERFET: the ‘International Force for East Timor’. Commanded by then Major General Peter Cosgrove, the multinational force sought to restore security in the region.

The first Australians arrived in Dili, East Timor’s capital, on 20 September 1999. Each of them, as well as their multinational counterparts, were issued a distinctive dark-green brassard. This brassard ensured that the members of INTERFET were identifiable to each other, the local population, and the TNI.

A DARK-GREEN BRASSARD

The INTERFET brassard was undoubtedly designed to stand apart from the pale-blue brassards issued to members of UNAMET. Its dominant symbol is a colourful emblem that portrays the territory of East Timor beneath a white peace dove. Surrounding this emblem are the words ‘PEACE’ and ‘INTERNATIONAL FORCE EAST TIMOR’. Above it, the abbreviation ‘INTERFET’ and—for Australian Defence Force personnel—the Australian National Flag. Naturally, each nation would affix their own national flag to the brassard.

The decision to use a dark-green and not khaki or DPCU (camouflage) cloth was likely a result of the international composition of the force. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the same dark-green cloth was used for the brassards issued to members of the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands, or RAMSI, in 2003.

Indeed, the use of brassards pre-dates INTERFET by nearly a half-century. As Senior Historian and Curator Brad Manera explains, “in the 19th century, British and Imperial soldiers had a regimental uniform that they wore for all occasions, on operations or out. These uniforms had rank and qualification badges attached permanently.”

However, during the 20th century, British and Imperial armies came to appreciate the benefits of a more functional, utilitarian uniform. As well as regimental dress, soldiers were issued a campaign uniform. Far more basic in their design, these uniforms often required the addition of temporary embellishments such as rank, qualification, unit identification and/or secondary appointments. “What began as simple armbands”, Manera continues, “had, by the 1950s, evolved into the military brassard.” With the introduction of DPCU (camouflage) uniforms, brassards have since become an integral component of military dress.

SWEEPING PATROLS

As well as facilitating humanitarian relief efforts, INTERFET sought to restore security to East Timor through vehicle-borne and on-foot patrols of the region. Liaising with Falintil, the military wing of the Timorese independence party, INTERFET had, by October 1999, achieved regional stability[3].

Anzac Memorial Guide and former Section Commander of ‘B’ Company, 3 RAR Milan Nettleton remembers patrolling in Dili shortly after disembarking from HMAS Tobruk (II):

“I recall an old bloke following our platoon on one of our first patrols in Dili up towards Cristo Rei of Dili. On one of our long halts he came into the centre to have a chat with the Platoon commander; one of our guys spoke Portuguese. This old bloke told us stories of how he had helped Aussie soldiers before in Timor when he was a kid.”

On 28 February 2000, Major General Cosgrove handed over military operations to UNTAET, the ‘United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor’. Established to administer East Timor’s territories and exercise legislative and executive authority during its transition to self-government[4], UNTAET continued until it was itself succeeded by UNMISET, the ‘United Nations Mission in Support of East Timor’ in May 2002, when the Portuguese colony of East Timor achieved formal independence. On 27 September 2007, East Timor was renamed Timor-Leste; the Portuguese name for the region.

AN UNEXPECTED CONTACT

On 10 October 1999, in the coastal town of Mota’ain, East Timor, a patrolling platoon of 'C' Company, 2 RAR came under the fire of a group of pro-Indonesian militia. In video footage depicting the contact[5], the men of 2 RAR—then part of INTERFET—can be seen taking cover before returning fire, killing one assailant and seriously wounding two others; all members of the Indonesian police.

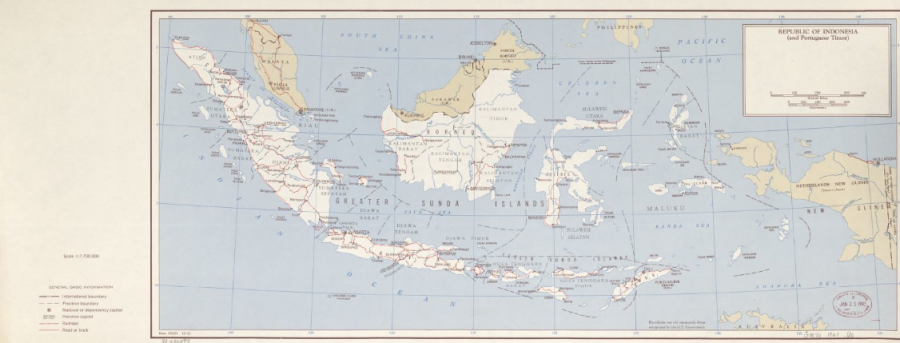

It later transpired that the firefight was a result of ‘bad intel’ on the part of the militia. According to the local commander of the Indonesian army, the men were using a Dutch map from 1933. INTERFET, by contrast, had employed an Indonesian map printed in the 1970s[6]. Whereas the Australians correctly regarded Mota’ain part of East Timor, the militiamen misguidedly perceived the town to fall west of the border.

Though no Australians were killed or wounded in the contact at Mota’ain, seven Australians lost their lives whilst deployed on peacekeeping operations in Timor-Leste.

Lest We Forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Australians committed to UNAMET were predominantly federal policemen and women.

[2] ‘Australians and Peacekeeping’, author unknown, Australian War Memorial, last updated 3 June 2021, accessed 4 October 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/peacekeeping

[3] ‘INTERFET’, author unknown, Australian War Memorial, last updated 20 September 2021, accessed 5 October 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/commemoration/interfet

[4] ‘UNTAET’, United Nations, last updated 2001, accessed 5 October 2021, https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/etimor/etimor.htm

[5] The footage was shared on Facebook by ‘Modern Soldier’ on 9 October 2018. See: https://www.facebook.com/ModernSoldi3r/videos/2rar-east-timor-border-contact-at-motaain-10101999/167224484208377/

[6] ‘Army’s hand seen in East Timor border ambush’, Joanna Jolly, The Guardian, 11 October 1999, accessed online 28 September 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/oct/11/indonesia.easttimor