On 19 September 1945, 81 Wing—comprising Nos. 76, 77 and 82 (Fighter) Squadrons and supported by No. 22 Repair and Salvage Unit, No. 481 (Maintenance) Squadron, and No. 381 Base Squadron—was committed as part of Australia’s air component to a British force of occupation in Japan; the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF).[1] Whilst the task of exercising military government over Japan was the responsibility of the United States, the BCOF was charged with maintaining law and order and supervising the demilitarisation and disposal of Japan’s war-making facilities.

Immediately following Japan’s surrender, the wider RAAF worked tirelessly to support the repatriation of POWs, time-expired servicemen and walking hospital cases. Meanwhile, the men of 81 Wing—still stationed at Labuan, a small island off the north-west coast of Borneo in the extreme southwestern part of the Pacific Ocean—were once again thrust into preparations for service on a new frontier. For the first time since the end of the Great War (1914-18), Australians would take part in the military occupation of a former enemy.

THE CALL FOR VOLUNTEERS

Service in Japan was not automatic. Rather, all participants, including the men of 81 Wing, were called upon to volunteer. Perhaps not surprisingly, after almost six years of relentless warring, the number of those willing to extend their service were somewhat limited.[2] For instance, of the 200 men of 77 Squadron, only 36 volunteered to serve with BCOF[3]. Nevertheless, the required numbers were eventually supplemented from elsewhere and the Wing was re-equipped with P-51D Mustang aircraft. By late September, operational conversion was begun in earnest.

PREPARING FOR JAPAN

Operational conversion was not without its setbacks nor its perils. Of the 97 Mustang aircraft issued to the squadrons BCOF service, 21 were lost, destroyed, or damaged while stationed at Labuan[4]. And, on 29 September 1945, the Wing suffered its first peacetime fatality.

Adelaide-born Alexander Hunter was just 19 years old when he applied for RAAF aircrew training in 1943. In June 1945 he was posted to 82 Squadron and landed with the squadron at Labuan on 3 July 1945. Unmarried and aged just 21 years, Hunter’s eagerness to continue his service beyond the Second World War is perhaps understandable. Sadly however, he would not live to see Japan.

According to his official casualty report, Hunter took off on a training flight around 11am on 29 September 1945 to conduct a battle climb to the service ceiling of the aircraft. Before take-off, he had attended a lecture on correctly fitting and supplying the aircraft’s oxygen mask.

At 11.30am Hunter’s Mustang was seen flying dangerously low above the treetops near the Sipitang army base at Brunei Bay, before disappearing. Despite extensive searches, neither Hunter nor his Mustang were ever recovered. His death was later ruled accidental, probably caused by unconsciousness due to lack of oxygen and a loss of control of the aircraft[5].

Alas, Hunter’s was but the first in a spate of accidents that plagued the Wing’s conversion training. Thankfully, most were not fatal; however, tragedy would strike again less than two weeks later.

On 12 October 1945, a Beaufighter from No. 93 Squadron, RAAF, attempted to take-off from Labuan’s rudimentary airstrip. Veering to one side, the aircraft collided with a dirt mound and struck four of 81 Wing’s Mustangs before crashing beside the strip alight. Although the pilot survived, five RAAF passengers on board could not be rescued in time and were incinerated in the inferno. Along with Hunter, their names would later be inscribed on the bronze panels of the Labuan Memorial, which was unveiled in June 1953.

ON TO JAPAN

In early February 1946, the transportation of BCOF volunteers commenced, and the main staff of 81 Wing embarked from Labuan to Japan by sea. Between late February and mid-March the pilots flew their own Mustangs to Japan via the Philippines. In late March the Wing was transferred from Okinawa to a former Kamikaze base at Bofu, in the Yamaguchi Prefecture, where the headquarters of BCOF’s Australian air component had been established. Tragically, misfortune marred the operation and the transfer flight claimed four more lives, including that of 30-year-old father-of-one Flying Officer John Allan.

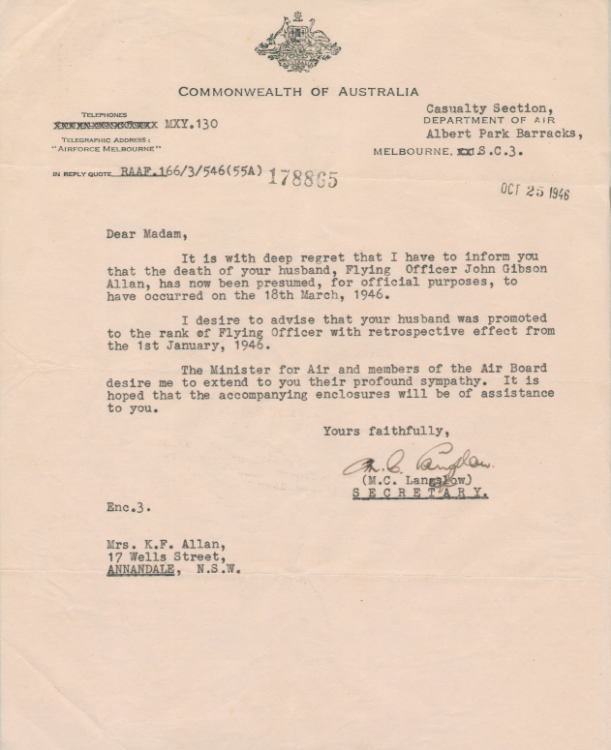

“IT IS WITH DEEP REGRET…”

"It is with deep regret" were the sombre words no wife, mother, sister, or next of kin ever wished to read in an official letter from the military authorities during the Second World War. Yet they were the mournful words that greeted Mrs Kathleen Jones, of Annandale, Sydney, in a letter of condolence informing her that her husband, Flying Officer John Allan, 82 Squadron, was reported missing, now presumed dead.

On 18 March 1946, Allan’s Mustang was one of thirteen aircraft engaged in the ferry flight from Okinawa to Bofu. Inaccurate forecasts saw the formation take off in bad weather, but not in conditions altogether unsuited for flying. However, as they approached Cape Tsuru the weather deteriorated further, causing one Mosquito and three Mustangs, including Allan’s aircraft, to go missing over the sea. Intensive search and rescue patrols were subsequently conducted by both British and Japanese search parties, but only two of the four pilot’s bodies were eventually recovered. No trace of Allan’s aircraft or remains were ever found.

Allan’s death widowed his wife of ten years, and made fatherless his only child, Jennifer. His name is also listed upon the honour roll of the Labuan Memorial to commemorate his service and sacrifice.

BOFU, JAPAN

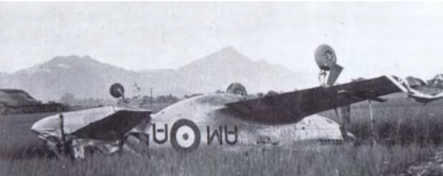

From 21 March 1946 to 12 March 1948, 81 Wing operated from the airstrip at Bofu. During this period, its Mustangs conducted surveillance flights over the prefectures of Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Shimane, Totlori and Western Shikoku. Intermittently bad weather and an unsuitable airstrip rendered non-operational flying infrequent. Fuel shortages further exacerbated the grounding of aircrew. As in Labuan, aircraft accidents were frequent, and in the short space of two years several Mustangs were entirely written-off.

In February 1947, a changeover of personnel saw a noticeable reduction in the squadron’s overall operational readiness. One of the newly posted members to 77 Squadron was Flight Lieutenant Cyril Nissen, a Second World War aviator and farmer from Queensland.

Flight Lieutenant Nissen was considered a proficient pilot. He had logged a total of 53.25 flying hours in the cockpit of the Mustang. Nevertheless, on 4 September 1947, Nissen was killed while attempting an emergency landing shortly after take-off. His Mustang bounced off the end of the runway and flipped into a muddy rice field. By the time the emergency rescuers could reach him, Nissen had already drowned. He left behind a wife and two young children.

Nissen’s body is interred at the Yokohama War Cemetery in Japan. His grave is one of eight dedicated to members of the RAAF who served and died in Japan between March 1946 and September 1947. Even so, it is only Nissen’s name that is listed on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Accidental deaths are always wretched deaths. And the inadvertent fatalities of servicemen and women in peacetime or on peacekeeping operations are always, in particular, deeply poignant. Yet these deaths sometimes get lost in our written histories, too often swamped by overarching official wartime mortality statistics, or at best confined to a footnote. However, their stories, like those interwoven in the rich history of 81 Wing, deserve to be told. Hunter, Allan and Nissen had served in and survived the Second World War and, tragically, by volunteering for further service, they did not live long enough to enjoy the peace for which they had so valiantly fought.

We will remember them.

Lest we forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid

FOOTNOTES:

[1] George Odgers, ‘The War Ends’, in Second World War Official Histories, Volume II, The Air War Against Japan, 1943-1948, Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1968 (reprint), p. 495.

[2] Despite this, between February 1946 and April 1952, approximately 16,000 Australians from all three services served as members of BCOF. The force ceased to exist on 28 April 1952 when the Japanese Peace Treaty came into effect.

[3] Wayne Brown, Andrew Cork and Colin Foggo, Swift to Destroy: An illustrated history of 77 Squadron RAAF, 1942-2012, (3rd edn.), 77 Squadron Association RAAF, p. 9.

[4] Figures compiled from the data provided at http://www.adf-serials.com.au/2a68c.htm , accessed 23 August 2021.

[5] Casualty report, 437963 Flt Sgt Alexander John Hunter Repatriation; Aircraft – Mustang A68-762 – Labuan – Borneo – 29 September 1945, accessed at https://www.naa.gov.au/ on 23 August 2021.