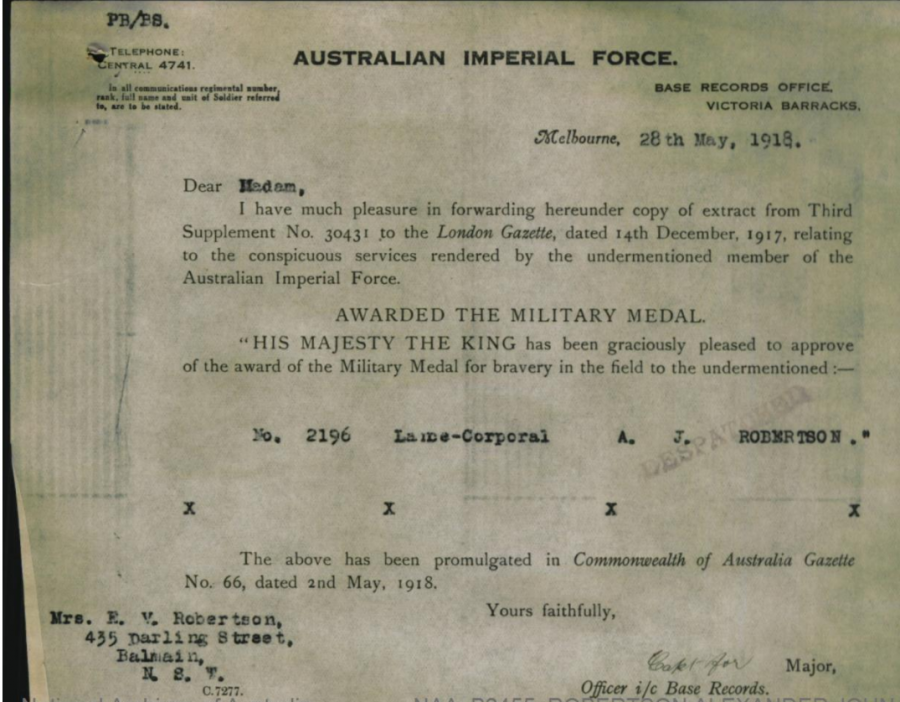

In 2019 the Anzac Memorial received a loan of four brass shell casings from the Great War. The loan from Shane Boyd and Fiona Boyd has since become a very generous permanent donation. The casings are from the ordinance fired by Krupp made, German 77 mm field guns. These were the most common field artillery used by the enemy on the Western Front and they were made in Magdeburg in Germany in 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1918. They belonged to 2196 Lance Corporal Alexander John Robertson, 1st Field Company Engineers, AIF who spent much of his war on the receiving end of these guns. The shell casings, three of which have been beautifully embossed with a leaf pattern over a pebbled background are a fine yet typical example of ‘trench art’; embellished casings became very popular souvenired artefacts during the Great War. One of them has the centrepiece from a Prussian Army belt buckle in the centre of it – “GOT MIT UNS” (God is with us) around a Prussian crown. Yet behind their remarkable story is another, perhaps more significant one. Robertson was at the Third Battle of Ypres at Broodseinde Ridge, east of Ypres, on 4 October 1917. For his actions on that day he was awarded the Military Medal (MM) for his bravery and devotion to duty during the attack.

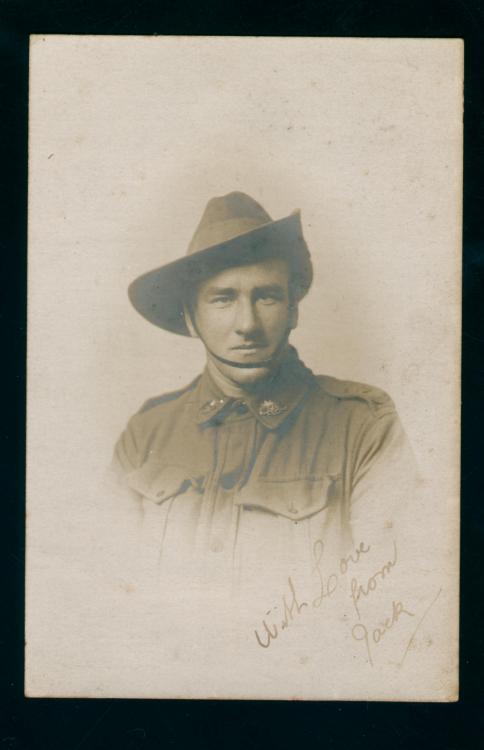

Alexander John ‘Jack’ Robertson was born in Waverly, NSW in November 1888. When he enlisted with the AIF at Holdsworthy on 9 August 1915 he was single and working as a plumber. Before he embarked from Australia two months later on 9 November 1915 he had married Balmain-born Esther Veronica Boughton and the couple were residing on Darling Street, Balmain. The new Mrs Robertson would not see her husband again until he returned from Europe in May 1919. Robertson was subsequently posted to the 1st Field Company Engineers as a sapper and spent most of the war in France and Belgium. Engineer units were attached to infantry brigades and their task was to provide specialist skills such as designing drainage for fighting positions, communication networks for trenches and tunnelling vital underground accommodation. As a trained plumber, Robertson’s skills would have been most useful indeed. On 30 September 1917 he was promoted to lance corporal. Yet it was his actions at the battle of Broodseinde Ridge five days later which perhaps held the most enduring significance of the war for him.

THIRD YPRES

The Third Battle of Ypres was planned to break through the strongly fortified German defences enclosing the Ypres Salient, a protruding bulge in the British front lines, with the intention of reaching German U-boat submarine bases on the Belgian coast.[1] The campaign was fought between September and November 1917 and over three long bloody weeks of fighting, Australian divisions participated in the battles of Menin Road (20 September), Polygon Wood (26 September), Broodseinde (4 October), Poelcapelle (9 October) and the First Battle of Passchendaele (12 October).

THE PLAN FOR BROODSEINDE RIDGE

The battle of Broodseinde Ridge, east of Ypres on 4 October 1917 was a vast operation launched by British General Sir Herbert ‘Daddy’ Plumer, commander of the British Second Army. It involved twelve divisions, including those of both I and II Anzac Corps armed with Lewis guns advancing on a front of thirteen kilometres. The attack was planned on the same basis as its predecessors; a step-by-step approach of limited advances preceded by heavy artillery bombardment. Once each attack had obtained its objective, the attacking troops were to be protected by further barrages whilst they consolidated their positions.[2] The battle was supposed to begin shortly before dawn at 6am yet the Germans had also chosen that same morning to launch an aggressive defensive strike. Forty minutes before the planned allied assault, the Australians, who formed the vital centre of Plumer’s twelve Division offensive were unexpectedly assailed by a mortar barrage which fell on the shell-holes where they were nervously waiting in the pre-dawn drizzle. It was a devastating stealth assault and twenty officers and a seventh of I Anzac Corps were killed or wounded before their own attack had even begun.[3]

‘COOLNESS AND COURAGE’

Alexander Robertson was one of a party employed on the construction of a strong point on Becelaere Ridge on the morning of 4 October 1917. Upon several occasions the Germans secured direct hits upon the trench, each time causing many casualties. Regardless of his own safety and the fact that an intense artillery fire was being directed on the spot, the diminutive plumber from Waverly (he stood at 5 feet, 3 inches) left his cover and proceeded to dig the wounded out and bandage them, in view of the enemy. He made several trips through the enemy barrage to assist the wounded to the dressing station, returning each time to recommence his work on the strong point. For his heroic deeds he was later awarded the Military Medal from the King. According to the official recommendation which was dated 9 October 1917, ‘throughout the day he displayed the greatest bravery and devotion to duty, and his personal example of coolness and courage were invaluable.’ Esther Robertson waiting patiently back home in Balmain was officially informed of her husband’s award by AIF Base Records Office in May 1918. Almost three years had passed since she had last seen him; today we can only imagine how she felt on receiving the extraordinary news.

THE BATTLE FOR BROODSEINDE RIDGE

‘An overwhelming blow had been struck and both sides knew it.’[4]

Despite the unexpected early onslaught, the Australians advanced and forged on through the barrage from the German 212th Regiment. Despite some very savage hand-to-hand fighting around enemy concrete pillboxes, the allied forces eventually gained all their objectives on the ridge. In the end they captured a total of 6,000 German prisoners and drove the enemy in front of them back more than 1,000 metres.[5] According to historian Chris Coulthard-Clark, ‘along the whole line the attack had been successful, thereby giving the British their first glimpse of the Flemish lowlands since May 1915.’[6] It was a battle that the official Australian War Historian Charles Bean noted as ‘the most complete success so far won by the British Army in France.’[7] However, it was not without great loss on both sides; the Australian divisions had suffered a devastating 6,500 casualties and German General Enrich Ludendorff wrote of 4 October 1917 that ‘we came through it only with enormous losses.’ Der Weltkrieg, the official German war history, similarly deeply lamented ‘the black day of October 4th.’ [8]

THE AFTERMATH

‘All through September and October the rain, shell-fire, mine explosions, aerial bombardment and horse-drawn heavy guns turned the green fields around Ypres into mud, water and general desolation. Teams of horses strained in mud and water up to their chests to pull the guns into position. Exhausted men sank in the mud and were drowned. Soldiers were heard to cry out: ‘I want to go home to my wife.’’[9]

Charles Bean noted that despite the intense fire laid on them before the start, the Anzac troops at the battle of Broodseinde Ridge ‘had never fought better.’[10] Yet the horrors of bombardment, barbed wire, remorseless machine gun fire and mustard gas created a veritable hell on earth at the Ypres Salient. Shellfire combined fatally with the rains to turn the fine Flanders soil into an ocean of mud which hampered the allied advance far more than German attempts to maintain their positions. In such appalling conditions, cases of influenza, dysentery and trench foot were rife. In early November 1917 Passchendaele finally fell to the Canadian Corps and on 12 November Sir Douglas Haig called a halt to the battle. Australian troops were withdrawn south to the relatively quiet Messines front where they would spend the winter of 1917-18. In November 1917 Alexander Robertson took leave and went to Paris and was later detached from his unit to undertake Lewis gun instruction. He was one of the lucky ones and upon his return to Australia in May 1919 he was declared medically fit, having survived the war uninjured. Perhaps he collected his dated shell casings to mark the trajectory of his war? Maybe they formed a personal memorial to all those colleagues he had helped and lost, so that he would never forget them? Today, a century on, we can only conjecture. Yet his story was an unusually fortunate one. In all, 38,000 Australian soldiers were killed, wounded or incapacitated in the Ypres Salient fighting in the second half of 1917.[11] Many of the dead remained where they fell, and their bodies were never recovered. The Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres lists the names of 55,000 men from around the British Empire whose bodies remain unknown to the Imperial War Graves Commission which was founded in 1917 to oversee the graves of the fallen.[12]

Lest we forget.

Article by Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Ypres is at the east end of the Gheluvelt Plateau in southern Belgium. The operations followed earlier campaigns over the same ground in October-November 1914 and April-May 1915.

[2] Also known as ‘bite and hold’ attacks. Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2001, p 130.

[3] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 4, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edition, 1941, p 844.

[4] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 4, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edition, 1941, p 875.

[5] A.K. Macdougall, Australians at War; A Pictorial History, The Five Mile Press, Victoria, 2002, p 111; Brad Manera et al, In That Rich Earth, The Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building, 2019, p 91.

[6] Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2001, p 133.

[7] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 4, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edition, 1941, p 877.

[8] Cited in A.K. Macdougall, Australians at War; A Pictorial History, The Five Mile Press, Victoria, 2002, p 111. New Zealand suffered 1700 casualties that day.

[9] C. M. H. Clark, A History of Australia, Vol VI, The Old Dead Tree and the Young Tree Green, 1916-1939, Melbourne University Press, 1987, p 65.

[10] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 4, The Australian Imperial Force in France 1917, 11th edition, 1941, p 875.

[11] The combined total of British and Dominion casualties has been estimated at 310,000; German losses were only just slightly lower.

[12] Some of these 55,000 men have since been recovered as mass graves have slowly been unearthed and remains subsequently reinterred.