Giggle suits were widely used by the army in Australia. Photographic collections record these uniforms being worn by men serving in line-of-communications roles like truck drivers and mechanics and garrison units such as artillery and engineers as well as the Volunteer Defence Corps.

A distinctive item of the giggle suit was a soft khaki cotton, floppy hat.

WHY IS THIS GIGGLE HAT DARK RED?

The answer reveals a complex and largely untold story about Australia in the Second World War. It illustrates how Australia treated its residents who had come from countries with whom we were now at war. These Australians found themselves labelled ‘enemy aliens’.

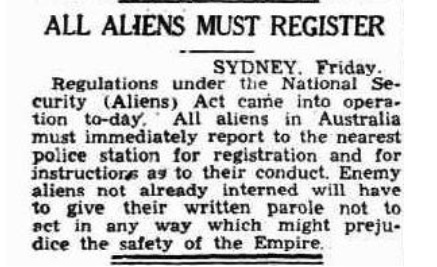

When Australia entered the Second World War in September 1939 Australians of German and Austrian ancestry had to register with the local authorities as potential enemy aliens. Many that were considered a risk to national security by spying or operating as saboteurs were locked up in Australian prisons until secure camps could be built.

In June 1940 Fascist Italy joined the war on the side of Nazi Germany. Suddenly thousands of Australians with Italian ancestry became enemy aliens and were likewise incarcerated. In December 1941 Japan entered the war on the side of Germany and Italy and so their citizens, resident in Australia, joined the ever-growing population in these ‘internment’ camps.

The intention of the camps was to concentrate and supervise the otherwise dispersed populations of enemy aliens. The earliest of these were known as concentration camps until the western Allies became aware of the use of the term in Nazi occupied Europe and the label was discontinued. By 1942 there were 18 major camps and hundreds of small camps, temporary barracks and registration stations set up across Australia to manage the lives of Australian residents that were deemed a security threat. These people needed to be transported, fed and clothed and ultimately guarded.

As the war dragged on Australian internees were joined by internees sent to Australia from Britain and other parts of the British Empire and by the US from some of its Pacific possessions. In 1943 there was a massive influx of Italian prisoners of war, captured in Africa and the Mediterranean, who were transferred to Australia from British holding camps in India. They joined Japanese prisoners of war who had been captured by Australian and US troops in New Guinea and on Guadalcanal or Japanese sailors, survivors of naval and air battles in the Pacific or over northern Australia.

While interning thousands of Australians and trying to maintain fighting forces at home and overseas as well as servicing the demand for artisans or manual workers on civil and military projects or as agricultural workers on food producing farms a severe shortage of labour was created. To satisfy this increasingly desperate need trusted prisoners were allowed, or conscripted, to fulfil these tasks.

Although an essential part of Australia’s war effort this prisoner labour force still had to be identified and monitored. Military authorities chose to dress them in a distinctive uniform so that they could not easily disappear into the civil population. The colour the army chose was similar to that used to dress German prisoners in Britain. In Australia it was referred to as magenta. The press described it as maroon or dark red.

WHERE DID MAGENTA UNIFORMS COME FROM?

Australian textile manufacturers were struggling to keep up with the demands of the military and civilian war industries. Tenders were sought from clothing contractors but were found to be far too expensive. Instead, the need was filled by units of the Australian Army’s Salvage and Recovery Section. They collected and repaired, recycled or disposed of items of kit deemed worn out by Australian soldiers. To meet the demands of those managing internees and prisoners of war the Salvage and Recovery Sections acquired, repaired and dyed Australian uniforms, occasionally supplemented by supplies of recycled civilian clothing, into the distinctive maroon (magenta) for issue to prisoners.

So, now that we have that background, let's take a closer look at this red giggle hat.

Comparing it with the khaki example we can see that it is definitely of the same pattern and style of manufacture. If we look inside the crown and on the underside of the brim we can make out blurred letters and numbers. Enough of the text survives to decipher that it was once a badly written identifier that read:

“E A Gardner

N 413372”

It is a name and an army number. The “N” before the numerals tell us that this is the number belonging to a soldier who is been called up or volunteered into the Australian Military Forces (AMF), from New South Wales. He has not joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). If he had joined the AIF the state letter prefix would have been followed by an “X”. If there had been an ”F” between the “N” and the “X” we would know that E A Gardner was a woman who would probably have enlisted to serve as a nurse or an army signaller.

Unlike the all-volunteer AIF, the AMF was made up of both volunteers and conscripts. The AMF could not be deployed outside Australia and its territories.

Using this evidence, we can search the Department of Veterans Affairs nominal roll for Australians who served in the Second World War and discover that Edward Arthur Gardner, from Boolaroo near Newcastle, NSW, was born on 14 December 1921. He was enlisted into the Australian army a week after his 20th birthday, just before Christmas and a fortnight after the Japanese entered the Pacific War in 1941[1]. Edward Gardner was assigned the number N413372 and was given the rank of Private in the AMF.

Edward Gardner entered his father Claude as his next of kin. If we cross check with the AIF database at the National Archives of Australia, we find a Claude Albert Gardner of First St, Boolaroo, who was a veteran of the Great War (1914-18). He had served as an infantryman with the 20th Battalion on the Somme in 1916 and was caught by shellfire at the Battle of Bullecourt in May 1917. He suffered shrapnel wounds to the arms, hands, chest and face. Blinded in the right eye he was sent home and granted a pension. He was 23 years old.

I have no doubt that this is the same Claude Gardner that Edward identified as his father when he enlisted. How did the wounded Great War veteran Claude react when his son was called to fight in a second world war?

N413372 Private Edward Gardner was posted to the 114th Australian General Transport Company. Did growing up a witness to his father’s injuries influence Edward towards service in a transport unit in the AMF rather than an infantry battalion in the AIF or did the army make that choice for him? We may never know.

What we do know is that Private Gardner’s unit spent most of its war providing motorised transport and supervision for internees and prisoners of war based at No.12 Camp on the outskirts of Cowra, NSW. The drivers and their trucks of the 114th Australian General Transport Company took internees and prisoners, who were trusted, beyond the camp’s perimeter, out on work details cutting timber or labouring on local properties.

The work may have been undemanding, but equipment and kit was still subject to the usual stresses of wear and tear. At some stage Private Gardner’s giggle hat was deemed unserviceable and so found its way to a unit of the Eastern Command Salvage and Recovery Section. It was just one of hundreds of thousands of articles of clothing that was dyed burgundy or maroon or magenta or dark red in huge vats, cured and then reissued to a German internee or an Italian, or possibly a Japanese prisoner of war.

It is interesting to speculate that if the Salvage and Recovery Section unit was operating nearby, Private Gardner’s hat may have returned to the area. If so, it is likely to been supplied to a prisoner at No.12 Camp which, in August 1944, became the stage for the largest prisoner of war breakout of the Second World War when over 1,100 Japanese prisoners rioted and charged the perimeter fence. Some breached the wire and rushed the Australian compound killing Australian guards. Others suicided within and without the camp. For weeks that area of New South Wales remained on high alert until all of the prisoners had either been recaptured, or their bodies recovered.

Whether this giggle hat was worn at Cowra in August 1944 or not we can only speculate, but in tracing its history we reveal a fascinating glimpse of wartime Australia.

Article by Brad Manera

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The Japanese entered the Pacific War by attacking British and Dominion troops in Northern Malaya on 8 December 1941. An hour and a half later, but on the other side of the International dateline, they attacked the US Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

FURTHER READING:

Bullard, Dr Steve, Blankets on the Wire (AWM, Canberra. 2009).

Fitzgerald, Alan, The Italian Farming Soldiers (Melbourne University Press. 1981).