The Anzac Memorial recently acquired this commemorative medallion mounted within a wooden presentation frame and stand. It belonged to Kenneth Henry Rowe of Glen Street, Granville, who served on HMAS Sydney II during the battle at Cape Spada. First made in 1941 by Amor Pty Ltd it was presented to the crew and staff of HMAS Sydney in February 1941 to commemorate one of the most significant sea battles of the war to date. The medallion was remade in 1944 from a cast of the initial issue and was presented in a blue faux crocodile skin felt lined box. Rowe’s medallion dates from the second press of 1944. The wooden frame holding this medallion is a mount of Rowe’s own invention. But why was the medallion re-issued in 1944 and what is its significance to the Anzac Memorial?

From 1940 until the Allied invasion of France in June 1944, the Mediterranean was a key theatre of war during the Second World War. Australian sailors served aboard Royal Australian Navy and Royal Navy warships operating out of Alexandria in Egypt. HMAS Sydney joined the Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet on 26 May 1940 and began patrol sweeps only hours after Italy’s declaration of war on 10 June 1940. On the morning of 19 July, HMAS Sydney was patrolling the eastern Mediterranean near the Antikythera Strait when she encountered and engaged Italian cruiser, Bartolomeo Colleoni and her sister ship Giovanni delle Bande Nere. The ensuing battle was fought off Cape Spada, on the north-west coast of Crete. Despite being outnumbered, in an extraordinary show of marksmanship HMAS Sydney succeeded in knocking out both boilers of the Bartolomeo Colleoni. The timely arrival of British destroyers with their torpedoes (so called ‘tin fish’) quickly sent the struggling Italian cruiser to the bottom of the sea. The severely damaged Giovanni delle Bande Nere was forced to flee. Whilst HMAS Sydney began picking up hundreds of enemy survivors from the water, the Italian air force bombed and strafed from the skies above, killing some of Bartolomeo Colleoni’s crew.[1] Kenneth Henry Rowe on board Sydney related the morning’s events in a letter to his parents at home in Granville, NSW. According to Rowe, ‘it was very exciting whilst the shooting and chasing lasted and to see a ship sink and burn at sea. It was terrible to see men wounded and dead in the water.’[2] Incredibly, despite the heavy bombing, HMAS Sydney sustained little damage, with just one hit to her forward funnel and only one minor shrapnel wound to a crew member.

News of the battle quickly spread and upon returning to Alexandria on 20 July, HMAS Sydney was met by a rapturous reception. It had been a swift and decisive victory for the RAN and the RN, and an ignominious defeat for Mussolini’s Italy. It was also a defining moment for the crew of Sydney, for this action earned them a reputation as brave and gallant sailors. Later, on returning to Sydney in February 1941, HMAS Sydney and her crew received a hero’s welcome home. But not before honouring the memory of her illustrious predecessor. On Monday 10 February as Sydney sailed passed Bradleys Head where the mast of the original HMAS Sydney, destroyer of the Emden stood, the Commonwealth flag was lowered as a tribute to the exploits of the new Sydney, whose ensign was dipped in return. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, ‘it was a silent commemoration of two great episodes in Australian naval history.’[3] It was only a short-lived silence however, because as Sydney sailed into the harbour, cheering and flag waving crowds in their thousands had massed around the harbour foreshore and a merry band played sea shanties to congratulate the now feted ship and her courageous men.

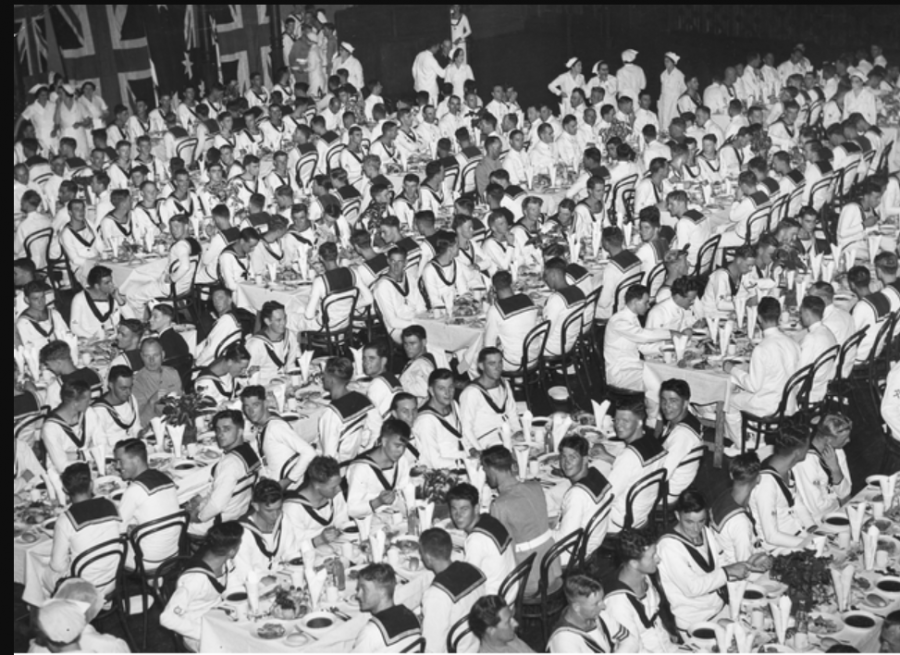

On the following day, the children of NSW were given the day off school and George Street was thronged with 200,000 adoring well-wishers as the staff, crew and ship’s band marched towards the Sydney Town Hall for a civic reception and luncheon. Here, the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Alderman Stanley Crick unveiled two large bronze plaques designed by Amor Pty Ltd. One featured an image of HMAS Sydney under full steam and with guns smoking, the other with an inscription commemorating the Mediterranean victory, framed above and below with laurel leaves. In addition to gifts of a rose bowl for the Officers' Mess and tankards for the Warrant Officers' Mess, Captain John Augustine Collins RAN and ten of his crew were presented with a small medallion version of the plaque to congratulate and commemorate their success in the Mediterranean.[4] Medallions for the remaining 603 crew were transferred to the ship’s safe, to be presented at a later date.[5] Following repairs in Sydney harbour, HMAS Sydney resumed wartime service in April 1941 and operated convoy escort duties between Australia and Singapore. From the original 614 crew who had seen action in the Mediterranean in 1940, only 252 re-joined her for service – the rest were posted elsewhere and replaced with just under 400 others.

Kenneth Henry Rowe was one of a number of civilian canteen staff who served on HMAS Sydney in the Mediterranean. Although not officially enlisted with the Navy during the Second World War, canteen staff were required to sail on RAN ships. Interestingly, civilian canteen staff serving with the Australian Army and with the Royal Australian Air Force were obliged to enlist. In times of action, such as on the momentous morning of 19 July 1940, canteen staff on board RAN ships acted as ammunition carriers and medical assistants as required. Later that year and very fortunately for Rowe, he left the ship at Western Australia before it set sail on its final fatal voyage. On the night of 19 November 1941, after a battle with the German cruiser HSK Kormoran, HMAS Sydney disappeared in the Indian Ocean with the devastating loss of all 645 crew. It was one of the worst disasters for the RAN during the war and the plight of the Sydney would remain a mystery for decades.

Kenneth Henry Rowe was still in his teens when he joined the complement of HMAS Sydney. The battle of Cape Spada was fought just eleven days after his twentieth birthday. Rowe left the ship after its service in the Mediterranean and, as a motor mechanic, was snapped up by the Australian Army Service Corps (AASC), the branch of service principally responsible for transport within the Australian Military Forces (AMF). On 7 January 1943, Driver Kenneth Rowe, volunteered for the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), losing his militia number N272626 and given the new identifier NX160493. Until discharged in June 1945, as part of the staged downsizing of the AIF prior to the end of hostilities, Driver Rowe drove and maintained heavy transport vehicles in the AASC, 7 Military District, (Northern Territory), a vital link in the line of communications to the war in the south western Pacific. [6]

Perhaps survivor guilt following the loss of Sydney with its entire crew and his mates had compelled him to transfer to the AIF? Survivor guilt was indeed quite common to many who had served on Sydney prior to her unexplained disappearance in November 1941. Maybe he simply wished to use his civilian skills in the war effort beyond our shores? Or perhaps, like many men during the Second World War, he was inspired by his own father’s service during the Great War?

Kenneth Henry Rowe’s father Cornelius Henry Rowe (1899-1975), a plumber’s apprentice, had enlisted as a teenager, and served as a private in the 1st Pioneer Battalion on the Somme in France in 1918. Private C H Rowe did not return home until September 1919. His English born wife Irene Mildred Rowe nee Cawley gave birth to Kenneth just ten months later. Whatever his reasons for enlisting in the AIF in January 1943, after the war, Kenneth married Sylvia Myfanwy Jones in Queensland in October 1946 and the couple spent the next twenty years living in Granville, NSW, later moving north to Wyongah. In his post-war life Kenneth Rowe worked as a carpenter. He died in November 2002 aged eighty-two.

Sadly, Rowe, like many other veterans and relatives, never found out what had happened to the men aboard HMAS Sydney. The wreck was finally discovered in 2008, 290 kilometres from Carnarvon off the coast of Western Australia and 22 kilometres from the sunken Kormoran. Most of the original first pressed Cape Spada commemorative medallions produced in February 1941 went down with the ship. In 1944, following requests from surviving ex-crew members and the next of kin of those who had perished, the medallion was remade from a cast of the initial issue. It has been estimated that less than one hundred were made.[7] Kenneth Henry Rowe was one of the recipients.

Despite being a second issue, the medallion is deeply significant to the Anzac Memorial. Soil from the Mediterranean battles and soil from the seabed of the Indian Ocean where HMAS Sydney was eventually located, are represented in the floor of the Hall of Service. This scarce object, provenanced to a local man from Granville in NSW is also a wonderful addition to the Anzac Memorial’s Royal Australian Navy collection and complements other artefacts related to HMAS Sydney before her tragic doomed last voyage in November 1941.

By Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

[1] In all some 550 Italians were rescued.

[2] ‘Very Exciting says Granville Youth’, Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 31 July 1940, p1 & p3.

[3] ‘Excited Crowds at Wharf’, Sydney Morning Herald, Tuesday 11 February 1941, p 9.

[4] Collins was a graduate of the inaugural entrants of the Royal Australian Navy College in 1913.

[5] Margaret Betteridge, Sydney Town Hall; The Building and its Collection, Council of the City of Sydney, 2008, pp 150-53.

[6] By transferring from the AMF to the AIF Rowe was volunteering to serve anywhere in the world.

[7] Clive Johnson, Australian’s Awarded; A Concise Guide to Military and Civilian Decorations, Medals and Other Awards to Australians from 1772 to 2013 with their Valuations, Second Edition, 2014, pp 679-80. See also Wes Olson, HMAS Sydney (II); In Peace and War, Hilton, WA, 2016.