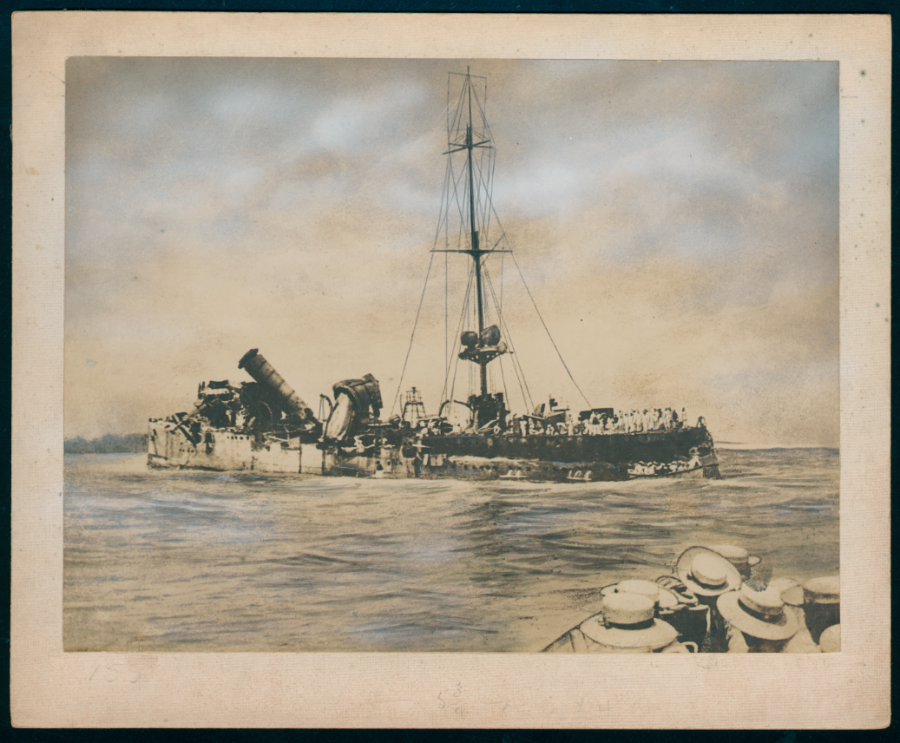

“The whole thing didn't last forty minutes, but it was a busy forty minutes. We hit the Emden about a hundred times, and fourteen of her shells struck us but most of them were fired beyond her range and the shells hit the side and dropped into the water without exploding."[1]

However, the apparent romance of Australia’s first naval victory dissipated quickly as Glossop’s unabashed recount turned macabre.

“…we sent boats ashore to the Emden. My God, what a sight! […] everybody on board was demented…Blood, guts, flesh, and uniforms were all scattered about. One of our shells had landed behind a gun shield, and had blown the whole gun-crew into one pulp. You couldn't even tell how many men there had been…

“They must have had forty minutes of hell on that ship, for out of four hundred men a hundred and forty were killed and eighty wounded and the survivors were practically madmen. They crawled up to the beach and they had one doctor fit for action; but he had nothing to treat them with—they hadn't even got any water. A lot of them drank salt water and killed themselves. They were not ashore twenty-four hours, but their wounds were flyblown and the stench was awful—it’s hanging about the Sydney yet. I took them on board and got four doctors to work on them..."[2]

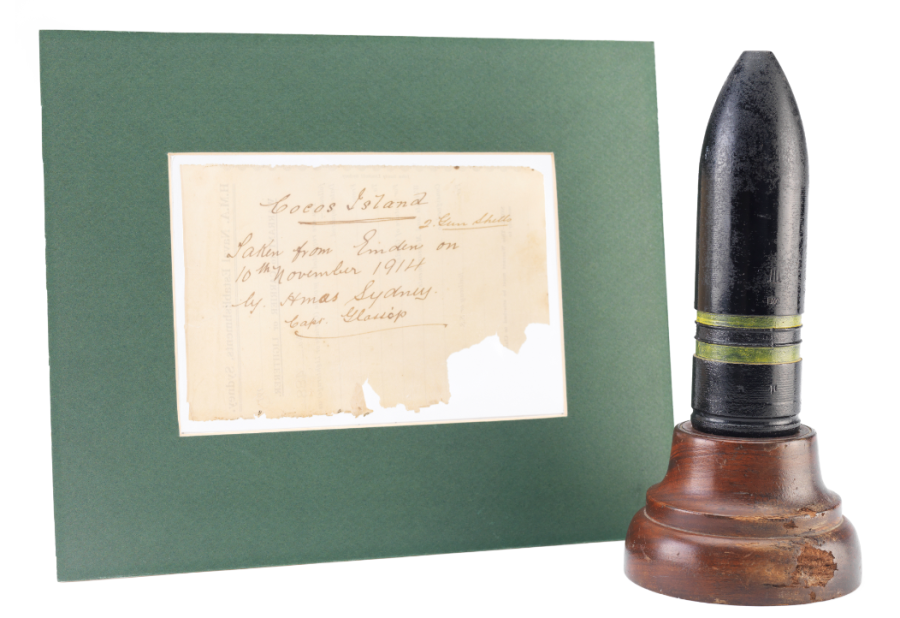

For Glossop, Sydney’s victory over the Emden on 9 November 1914 was his first and last sea battle; the remainder of Sydney’s war service was, comparatively, a ‘protracted anticlimax’[3].

STOKER STAN NEWTON, RAN

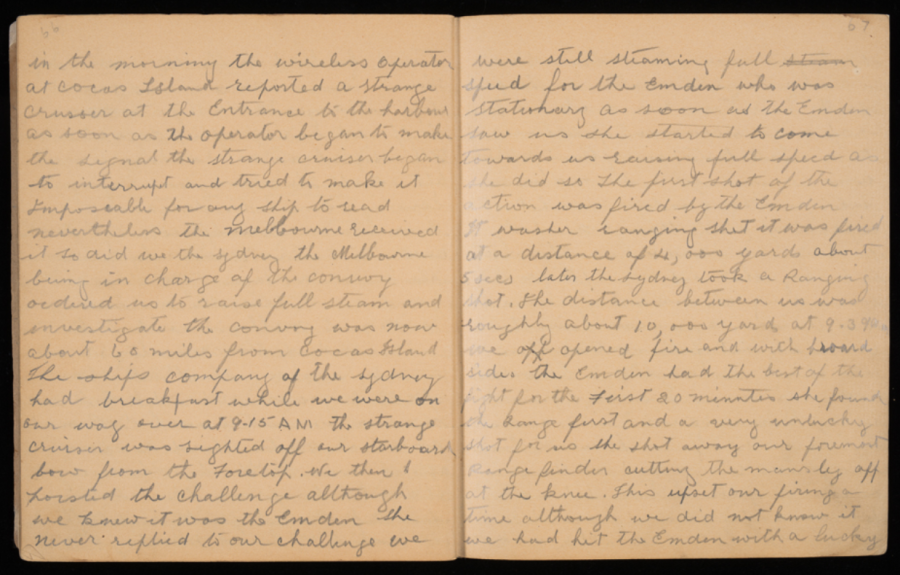

Meanwhile, 21-year-old engine room stoker Stan Newton recounted in his personal diary his own version of events. Just days after the engagement he wrote:

"The first shot of the action was fired by the Emden. It was her ranging shot […] The Emden had the best of the fight for the first 20 minutes […] She shot away our foremast and range finder, cutting the man’s leg off at the knee. This upset our firing a time. Although we did not know it, we had hit the Emden with a lucky shot from our first broadside…

“A minute or so later a shrapnel shell burst on our deck and laid 7 of a gun’s crew out of action. 2 of these died later. One of these fellows was a gunlayer. A second or so later another gunlayer was hit with a piece of shell through the body. He lingered for 48 hours. The next unlucky shot hit our after control, wounding the control officer and 4 of the men; one man being blown completely out of the control. This man had his right eye blown out and was wounded in the leg and body. He recovered and managed to carry the officer below. The Emden firing was very good at the beginning of the action but soon fell away […] It was now our turn to make good, which we did with a vengeance.”[4]

For Newton—as with Glossop—the Sydney–Emden engagement proved his last sea battle. But it was certainly not his first taste of naval warfare.

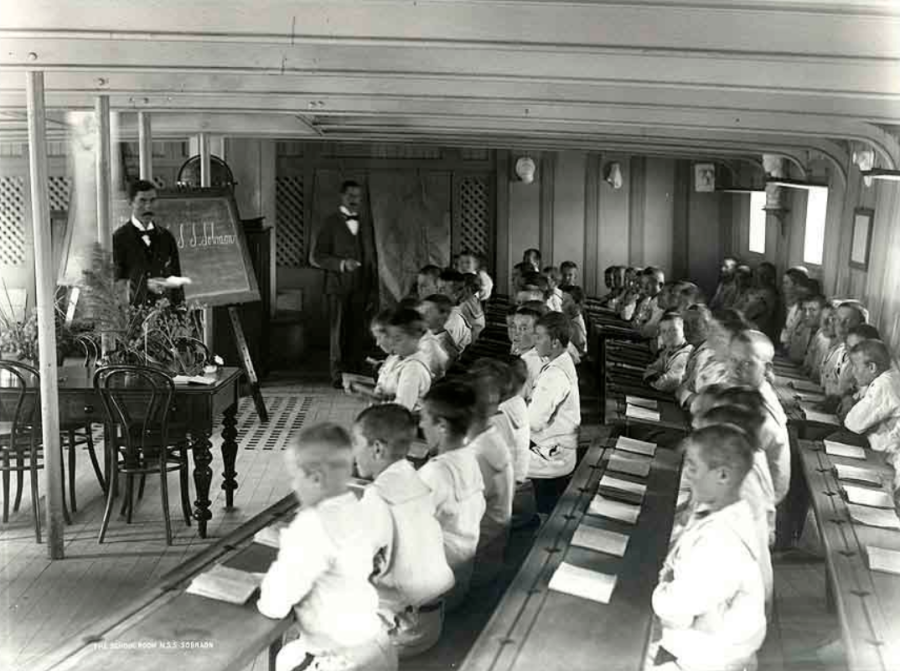

"SUBMITTED TO SEA"

Stan Newton was born in Sydney in 1893 to Henry and Agnes Newton. Sadly, in 1905, Newton’s father died, causing the soon-to-be teen to act out. Just four months after his father’s death, Newton faced Sydney’s Children’s Court on his third conviction of theft. He was deemed “a very bad boy who keeps bad company” and “entirely out of his mother’s control”[5]. In an effort to reform the disturbed youth, the Court entered him into service on the NSS Sobraon, a reformatory training ship that housed up to 200 troublesome boys.

In November 1909, after his chance at an apprenticeship resulted in a further charge of misconduct, Newton was once again “submitted to sea”. In 1911, the Sobraon was abandoned. Now an adult, Newton decided to join recently formed Royal Australian Navy (RAN).

A FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT OF LIFE AT SEA

Newton’s diaries provide remarkable first-hand testimony of some of the RAN’s pivotal pre- and post-war events. He was aboard HMAS Sydney when it arrived in Australia with the RAN’s first fleet in 1913. In 1914, he went with it to Singapore to provide escort to Australia’s first submarines—the doomed AE1 and AE2—and even bore witness to the HMAS Australia mutiny in 1919.

Principally, and perhaps more importantly, his diaries account for his wartime experiences.

Following Australia’s declaration of war, Newton served aboard the Sydney as she conducted punitive expeditions against the enemy in German New Guinea. In October, she returned home to provide escort to the First A.I.F. Convoy[6]. It was during this convoy that Sydney encountered and destroyed the SMS Emden.

Less several brief shore postings, Newton spent the majority of his wartime service coaling the mighty engines of HMA Ships Sydney and Encounter. Sadly, it was this very service that ultimately catalysed his premature death.

In 1920, aged just 26 years, Stan Newton succumbed to nephritis. Unlike his brother Rupert, buried in France while serving with the 17th Australian Infantry Battalion, Newton rests eternally in his home city of Sydney. His gravestone at Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery bears the inscription:

Stanley D. H. Newton

Stoker. No. 3843, late H.M.A.S. "Sydney," & "Encounter." Died in P.A.H. Sydney. Our son & brother.

Lest we forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A.B. ‘Banjo' Paterson, Happy Dispatches: Journalistic pieces from Banjo Paterson’s days as a war correspondent, Sydney, Landsdowne Press, 1980, p. 65.

[2] Ibid, p. 65.

[3] Denis Fairfax, Glossop, John Collings (1871-1934), Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/glossop-john-collings-6403, accessed 2 November 2021.

[4] Excerpt as transcribed from the diary of 3843 Stoker Stanley Douglas Hammond Newton, RAN. Anzac Memorial Collection

[5] State Archives NSW; Series: NRS 3902; Item: 8/1750; Roll: 2889.464.

[6] The convoy of Australian and New Zealand soldiers, so named the First A.I.F. Convoy, comprised 38 Australian and New Zealand transports. To protect the otherwise defenceless fleet against the threat of von Spee’s East Asia Squadron (and especially the Emden), a substantial escort of warships was assigned the convoy. Among them was HMAS Sydney, a Town Class light cruiser. The First A.I.F. Convoy set sail from King George Sound, Albany, on 1 November 1914.