The Anzac Memorial was intended to be a memorial to all Australians who lost their lives in service during the First World War, not just the soldiers from the Gallipoli campaign to whom the term “Anzac” was first attached. The imagery and symbolism in the statues and artwork, and the inscriptions in the building itself, reflect all of the campaigns involving Australians and all of the armed forces and auxiliary services that took part.

The Book of the Anzac Memorial, published by the Trustees in 1934, makes this intention clear; it reiterates that in addition to being a “memorial" it was intended to provide a place for all returned soldiers, sailors and nurses to use.

The dream of building a memorial to honour the Anzacs from New South Wales was first formulated in 1916. The building was conceived as a memorial for members of the AIF who “won for Australia its place among nations” through the courage and dash they displayed. However, government restrictions, lack of money and divisions among the returned servicemen and the wider community about the style and purpose of war memorials combined to prevent any progress on collecting further subscriptions or producing a shared concept for the Anzac Memorial building. Also, the several returned soldiers organisations in New South Wales and the federal RSSILA, based in Melbourne, held different opinions about the course that should be taken.

The controversy raised by the two conscription referendums held in October 1916 and December 1917 politicised the soldiers’ organisations. The loss of 23,000 Australian officers and men in seven weeks of fighting on the Somme had driven the first conscription proposal. Prime Minister Billy Hughes believed a compulsory call-up was needed to replace these unsustainable losses. The first referendum was lost by a narrow margin, and the No vote in the second was slightly larger. So Australian forces continued to rely on volunteers. Unfortunately, the campaigns had created deep divisions in Australian society that lasted well into the peace.

On 2 August 1918 the RSA organised another collection day for the Memorial building. This time, however, rather than concentrating on the original Anzacs, the money collected was intended to honour all who served in the AIF during the war, including those who had returned. Elaborately organised, the day featured such activities as processions of schoolchildren, callisthenic displays, stalls, dinners, slide shows and other entertainments; the day attracted good public support and raised £45,300.23 Once the war ended on 11 November 1918, the organisation of the repatriation of thousands of soldiers took precedence over war memorials. At the same time the restrictions imposed on public meetings during the worldwide Spanish influenza pandemic limited the amount yielded by the 1919 appeal to just £5,700. Nevertheless, the £60,000 collected in total was considered sufficient for the purpose, although it paled into insignificance when compared with the £250,000 gathered for the same purpose in Melbourne. Further progress on the New South Wales Memorial would depend on legislation, and that would require a greater degree of consensus than existed in the troubled months of 1919.

The RSA (NSW) remained firm in its determination to erect a fitting memorial building for their fallen comrades. However, its rationale developed as time went on. In the second Anzac Memorial book, published in 1917, the president, Senior Chaplain Dean Talbot, stated that the chief reason for forming the association was to foster a continuance of the spirit of comradeship created in camp and field: “There is no comradeship to be compared with it in the world and it is worth carrying over into civil life”. The second aim was to keep the memory of their fallen comrades “evergreen”; the third was to help solve the problems of repatriation and care for those who were partially and totally incapacitated.24 In 1918 the financially troubled RSA managed to survive only by converting itself into a branch of the RSSILA.

Nevertheless, the proposed dual purpose of the Memorial building was retained. As stated in the published aims of the RSSILA in 1918, the provision of areas to offer practical help to returned soldiers continued to be important:

- the building was to be a memorial for those who died;

- it was to be architecturally worthy of its high purpose;

- it was to provide headquarters for those working to assist widows and children of those who were killed and also, those AIF members who returned;

- it was to house the records of the AIF;

- it would be a meeting place and a source of assistance with repatriation; and

- it would provide a centre for any later campaigns on behalf of the AIF and their dependants.

THE ANZAC MEMORIAL (BUILDING) ACT 1923

Attempts to pass the legislative authority to build the Anzac Memorial began in 1919 but did not succeed until 1923. The original proposal, which combined constructing the Memorial with the incorporation of the New South Wales branch of the RSSILA, was the main cause of the early failures. The large Melbourne-based federal body did not represent the people who had collected the Memorial funds. Another setback was the rejection of the original proposal for membership on the Board of Trustees. As was customary, those nominated to administer the Memorial fund were mainly political leaders – the lord mayor, bankers and businessmen – and initially included only one returned soldiers’ representative from the RSSILA. These arrangements did not satisfy the other returned soldiers’ groups.

Success came through an agreement to allow three returned soldiers’ associations a place on the Board of Trustees, and to give all the returned soldiers’ associations the opportunity to have office space in the building. Importantly, it was determined that the site for the Memorial had to be approved by both houses of the New South Wales Parliament, but it did not specify what form the Memorial should take.

Assented to on 12 December 1923, the Anzac Memorial (Building) Act incorporated the Board of Trustees which was to take responsibility for the building, both during and after construction. The Act transferred funds raised for the Memorial during 1916, 1918 and 1919 to the Trustees, who comprised the Premier of New South Wales, the Leader of the Opposition, the Lord Mayor of Sydney, the Public Trustee, the Deputy Governor of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, the President of the New South Wales branch of the RSSILA, the President of the Limbless and Maimed Soldiers’ Association and the President of the TB Soldiers’ Association. The Act did state, however, that the building “would not only serve as a memorial of the achievement of the Australian Imperial Force, but would also provide returned sailors and soldiers a place for rest and recreation”.

CHOOSING A SITE

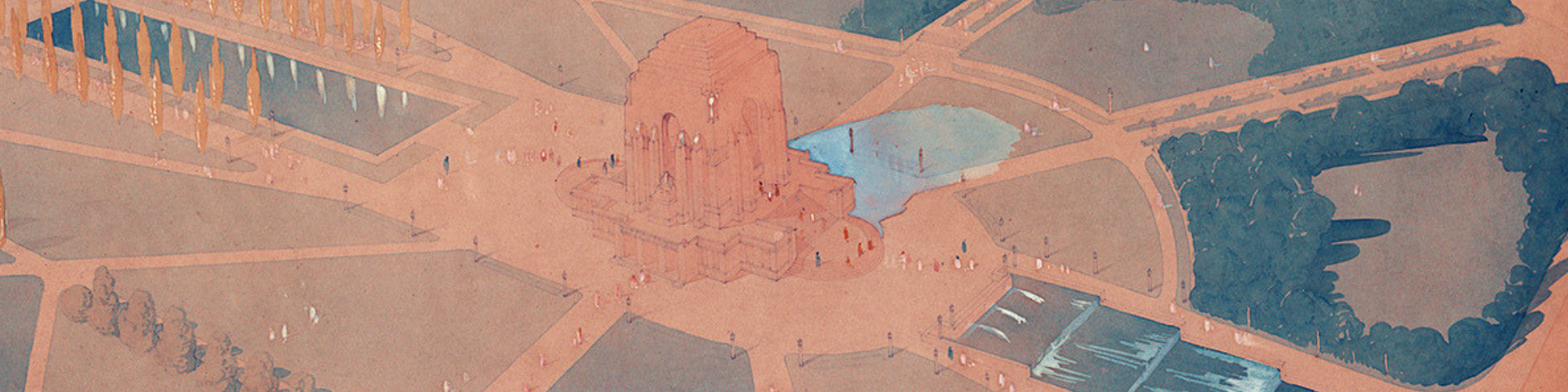

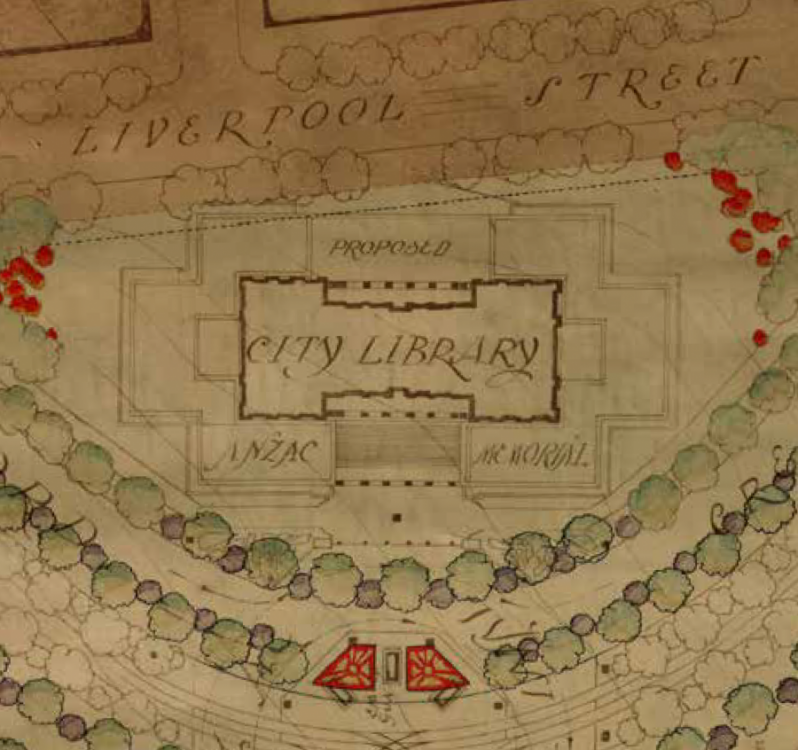

After 1919, all the states’ war memorial building committees were required to seek expert advice from a War Memorials Advisory Committee comprising representatives from the Town Planning Association, Institute of Architects (NSW), Royal Art Society, Society of Artists and the National Art Gallery (NSW). Hyde Park was the first place suggested for the Memorial, in May 1918. Other site suggestions included Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, Park and College Streets (spanned by arches), a central courtyard between the Mitchell Library and Public Library, Martin Place, the entrance of Anzac Parade (gates), Harbour Bridge Road, Upper Fort Street, Fort Denison, the bowling green in College Street, Observatory Hill, the cliffs at South Head, Church Hill, the Parliamentary tennis court and bowling green, Cook Park, Park Street (spanned by a building), the Botanic Gardens, Admiralty House, or the centre of the Domain. The structures proposed for these various sites ranged from arches similar to the Arc de Triomphe or a tower similar to the Eiffel Tower to a carillon or a cenotaph. The proposal to use part of Hyde Park was supported by the Institute of Architects and former city surveyor Norman Weekes, who won the competition to redesign the park after it had virtually been destroyed during the construction of the city railway. As the underground tunnels for the railway had been formed by extensive excavations from ground level, much of the vegetation had been destroyed. By the time the winning design was announced in 1927, the space had been reduced to a kind of desert. For example, the southern end had a mountain of excavated soil and the south-west corner had been a railway construction site for more than 12 years. Weekes, with assistance from architect Raymond McGrath, produced a strong plan with two axial avenues running north to south and east to west, the latter being in line with the transept of St Mary’s Cathedral. Weekes envisaged the intersection of these avenues as an ideal site for a commemorative column and balanced that with an Anzac Memorial at the southern end. At the time, the exact form of these focal points was unknown. Weekes connected the two halves of the park by a bridge over Park Street, which itself remained a thoroughfare. The competition judges supported Weekes’s concept of using monuments as focal points. Seeking authorisation to use the Hyde Park site for the Anzac Memorial, the Trustees laid Weekes’s plan before the state parliament in 1928. They had already gained support from the Sydney City Commissioners and obtained a licence for permissive occupancy from the Lands Department that still controlled the park. Parliamentarians debated the matter along party lines during late 1928 and early 1929. Eventually the Hyde Park site was chosen, in spite of strong objections to reducing the area set aside as the city’s breathing space. When the site gained parliamentary approval on 19 March 1929, the area ultimately dedicated to the Memorial was limited to 100 square feet. Then the Advisory Board for the Hyde Park Remodelling, which included Norman Weekes, discussed the monument’s site at a City Council Conference on 3 May 1929 and chose the southern end of the park for the building. Weekes probably influenced this decision, but others opposed it. The National Council of Women and Anzac Fellowship of Women rejected the Hyde Park site because it was not sufficiently commanding, while artist Julian Ashton pointed out that skyscrapers would soon overshadow its position. Another war memorial, bequeathed to Australians by the late J.F. Archibald, co-founder of The Bulletin, was intended for the Botanic Gardens or another Sydney public garden, to commemorate the association of Australia and France in the Great War. The memorial was to be a bronze sculpture designed by a French artist and incorporated into an electrically lit fountain. Artist François Sicard, who had won the Prix de Rome in 1891 was chosen to create the work. However, a site for the bronze and granite sculpture could not be found in the Botanic Gardens. The Public Trustee requested the site of Weekes’s proposed column at the northern end of Hyde Park. The Archibald Memorial Fountain was completed and transferred to the city on 14 March 1932 – at about the same time that work began on the Anzac Memorial building at the southern end of the park.

DETERMINING THE STYLE OF THE ANZAC MEMORIAL BUILDING

While the various sites were being debated, those discussing the style of the building divided into opposing soldiers’ and women’s groups, who supported utility and beauty respectively. Most returned soldiers wanted a building that would meet their immediate needs, while women’s groups tended to favour a structure that would be noble and commemorative. Architect and publisher Florence Taylor expressed the latter view in 1923:

This is a most opportune time to erect something of a magnificent and monumental nature whose noble purpose, symbolical interpretation and intense beauty would bring comfort to the disconsolate hearts of the mothers, elevate the sentiments of the people and enrich the city.

Another who objected was Dr Mary Booth, who had been a prominent leader of the war effort on the home front. During the war, she had raised money for the Soldiers’ Club that she established at the Royal Hotel, in George Street, for soldiers who needed a place to stay in the city. In 1921 Booth founded the Anzac Fellowship of Women, and campaigned strongly for “a sacred centre for ceremonial occasions only”, nominating a site near Admiralty House as the most worthy site for it. Booth also led the Centre for Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers, which created a monument for the gate to Woolloomooloo Wharf, where women had farewelled their loved ones during the war. Another state women’s group that planned a memorial soon after the war comprised those who “have throughout supported and worked for the Memorial to a degree beyond all praising”. It selected a design by the first recognised female sculptor in New South Wales, Theo Cowan, but lacked the funds to build it.

Historian Ken Inglis credits Booth’s long campaign with the final decision about the character of the Anzac Memorial building. After ten years of debate, on Anzac Day 1928, the RSSILA and the disabled veterans bodies all agreed that the building “should be commemorative rather than utilitarian”. As the RSSILA state president Fred Davison expressed it, the League had agreed to a “shrine of remembrance” such as their Victorian counterparts had begun to build. The decision was perhaps partly due to the ceremonial role already established for the Cenotaph. However, the soldiers’ needs were not entirely abandoned; in the spirit of compromise, one-seventh of the funding was allocated to incorporate offices, where the returned soldiers’ organisations could look after their members.

THE CENOTAPH, MARTIN PLACE, SYDNEY

The uncertainty about both site and style of the Anzac Memorial left Sydney without a focal point for the Anzac Day commemorations in 1925. The Lang government responded to the urging of the New South Wales branch of the RSSILA, whose membership was so strong that it was now a powerful political force, by donating £10,000 for a cenotaph in Martin Place. An article by Fred Davison, published soon after Armistice Day 1924, seems to have been the deciding factor. Davison wanted a memorial stone or a cenotaph similar to that erected in London’s Whitehall. The dominant members of the cenotaph committee, former president of the RSA (NSW) Hugh D. McIntosh and Davison, requested a memorial design from English sculptor Sir Bertram Mackennal, then visiting Australia. Mackennal, who had been responsible for the Whitehall cenotaph, produced a more modest version of the memorial he had designed for Brisbane.

Mackennal’s design featured a plain rectangular tomb with statues of a soldier and sailor at either end, the cenotaph bears the inscriptions “To Our Glorious Dead” and “Lest We Forget” on its longer sides. It was positioned in Martin Place near the GPO colonnades, on a site where wartime appeals and recruitment rallies had been held. This was also where the Armistice Day crowds had gathered on 11 November 1918. Consecrated on 8 August 1927, the Cenotaph became the focus of Anzac Day ceremonies.

The Anzac Day Dawn Service at Sydney’s Cenotaph still attracts large crowds every year. The Cenotaph is also the centre for many other wreathlaying ceremonies annualy.

THE ANZAC MEMORIAL DESIGN COMPETITION

The competition for the design of the Anzac Memorial building was announced on 13 July 1929, and the conditions were published in that month’s editions of Building magazine and Architecture, the New South Wales Institute of Architecture journal. Entrants were required to be Australians qualified to work as architects within or outside New South Wales, the latter being required to register in the state if they won. (By definition, “Australians” included those born as British subjects who had worked in this country as a principal or assistant architect.) Competitors could confer with an Australian sculptor, either while designing their competition entry or during its construction.

The Anzac Memorial Trustees organised the competition in two stages, the first being to indicate the broad concept of the designs. After these broad concepts were assessed, seven entrants would be invited to elaborate on their plans. All entrants had to register by 30 January 1930 and present their entries two weeks later. The judges were Professor Alfred Samuel Hook, past president of the New South Wales Institute of Architects; Professor Leslie Wilkinson, Dean of the Sydney University Faculty of Architecture; and E.J. Payne, the Public Trustee, who was also an Anzac Memorial Trustee. The prizes were £250, £200 and £100, with £75 for all others who reached the second stage. The winner of the first prize would become the Anzac Memorial architect. The cost of the building was limited to £75,000, calculated at rates current at the time of entry. Presented on canvases of calico or linen, the designs had to be accompanied by a report clarifying the architect’s intentions and providing an estimate of cost. Entrants could also submit small models.

In addition to the memorial itself, which could take any commemorative form the building must also provide office accommodation for the RSSILA, the TB Soldiers’ Association and the Limbless Soldiers’ Association. As the remodelling of the southern part of Hyde Park was not yet finished, the Trustees provided competitors with a plan of the future layout. Both the Anzac Memorial Trustees and the City Commissioners had already agreed that the most appropriate position would be at the intersection of the park’s ‘Main Avenue’ and the axial line of Oxford Street, but they were prepared to allow some latitude. This site was currently covered by the spoil dump from the city railway excavations, which had revealed that bedrock lay 10 feet (3 metres) below the normal surface of the park.

THE MEMORIAL'S DESIGN

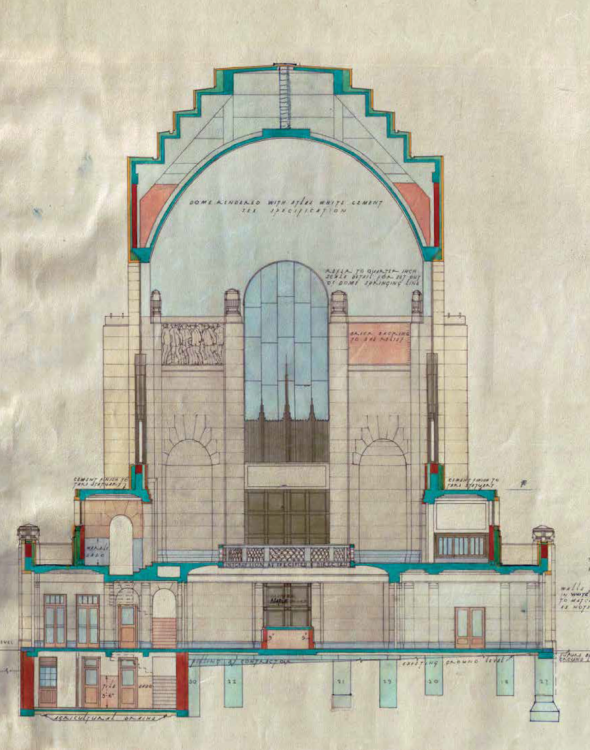

In his entry, Dellit submitted a model, with photographs of it from all angles, and 17 drawing sheets including an aerial perspective and an isometric section. His “Descriptive Elevation” was a labelled diagram that explained the statuary and inscriptions that he intended to place above both entrances to the Memorial. The statues on the four corners at the top of the edifice were to be the “Four Seasons, representing Eternity”. Lower down on the 16 buttresses were “symbolical figures representing the arts of war and peace” and level with the top of the buttresses were “bas reliefs of Australian soldiers”. On the eastern and western sides, there would be “symbolical groups” of statuary – one representing “peace crowning endurance and courage”, the other “victory after sacrifice”. Above the northern and southern doors, there would be classical quotations. No. 1 Entrance – North Elevation: "Never was a campaign that showed more gloriously the soldiers valour than this, wherein each day they faced the foe and the stress of storms and great and dire hardships they endured so nobly that speech can lend no lustre to the splendour of their deeds." (Hyperides, Funeral Oration, Section 23) No. 2 Entrance – South Elevation: "No bond seems firmer, none more beloved than that which binds each and all to our country – dear are parents, dear are children, kin, and friends: but every affection that touches each one, our country holds in one embrace." (Cicero, De Officiis, Book 1, Section 17 42) Dellit rejected the popular memorial figures that already had appeared in many suburbs and towns; “men standing dully at ease adjoining some obelisk or some massacred masonry, do not appeal to me,” he wrote. Instead, he offered an abstract image of the “nobler attributes of human nature evidenced during the torrid war years”. He placed another symbolic group at the centre of the monument. He intended this figure to be a hero (an Australian soldier) – sculpted in the Greek manner – who was dying after having killed a “colossal” and “repulsive” bird of prey (symbolising the war). Over this would be a sorrowing woman (Australian motherhood) nursing an infant (future generations for whom the hero had made his sacrifice). The chief vantage point from which to observe this group was above.43 In Dellit’s own words, “ENDURANCE, COURAGE AND SACRIFICE – these are the three thoughts which have inspired the accompanying design, and it is around the last mentioned that it develops”. He explained that the central sculpture “Sacrifice” was placed in the lower chamber “like a famous French tomb” (Napoleon’s tomb) to “offer visitors an opportunity for a quiet, dignified, physical and mental acknowledgment of the message” as they bowed their heads to look at it. Had there been sufficient funding, he would have provided additional sculptures on top of the monument, and he believed that future generations might add some to the terraces.44 As it was, the £51,000 he budgeted for the building and the £23,000 for the sculptures seemed less than adequate for his ambitious plans, when compared to price estimates calculated by other entrants for buildings using less material.

In designing the Anzac Memorial, Dellit used strong imagery to express the collective sense of mourning over the deaths of so many young men from New South Wales. The building as a whole makes a strong statement through its very solidity. Art Deco flourishes, such as the ziggurat-styled apex and the amber glass window panels etched with the rising sun and decorated with skyscraper-shaped forms at the base, place the exterior of the monument squarely in the inter-war period. The final form of the sculpture must be credited to sculptor Rayner Hoff, whom Dellit engaged after winning the competition. It was Hoff who persuaded Dellit to change his own proposals for sculptures, which relied on obscure imagery and symbolism. Hoff greatly strengthened the external imagery by replacing Dellit’s seasons and sculptures representing the arts of war and peace with figures representing all branches of the armed services. As a result, the figures on the buttresses and the reliefs over the doors between make the building’s purpose very clear. However, the Pool of Reflection that mirrors the building on the northern side represents Dellit’s call for passers-by to stop and remember.

Similarly, while the central sculpture, Sacrifice, at the heart of the building is Hoff’s, the form of the interior, itself very emotive, is Dellit’s. Here is ample evidence of his architectural imagery. He used impressive staircases, flanked by memorial urns, to lead the visitor up into the Hall of Memory. Once there, they must bow their heads to look into the Well of Contemplation in order to contemplate Sacrifice, in the Hall of Silence below, and look up to see the dome decorated with 120,000 golden Stars of Memory, each representing a serviceman or woman from New South Wales. In this manner, Dellit’s architecture and Hoff’s sculptures greatly enhance each other to provide an artistically integrated emotional message.

In 1930 architect Bruce Dellit commissioned Rayner Hoff to design the sculptures for the Anzac Memorial. He felt Hoff could supply the “dynamism” needed to complement the modernity of the construction.

Two years later, when the finished sculpture designs were exhibited in Sydney, the magazine Art in Australia devoted the whole of its October edition to Hoff. An article by Lionel Lindsay revealed that Hoff had significantly changed Dellit’s original conception for the monument’s central sculpture. Hoff designed a group of three female figures and a baby (representing mothers, sisters and wives and future generations), combined into a single column like a Greek caryatid; these mourning women supported a shield bearing a naked dead soldier.

The installation of external sculptures of members of the armed services and the medical corps was another major design change that emanated from Hoff. It was Dellit, however, who resolved to use cast granite rather than bronze for the figures on the buttresses, so that they would “appear as though growing forth from the stone surface”. This latter change emerged during the design phase.

Also exhibited in 1932 were the models for the two massive bronze sculptures by Hoff that were intended for placement in front of the east and west windows as substitutes for Dellit’s Peace Crowning Endurance and Courage and Victory after Sacrifice. These were Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914 and Victory after Sacrifice 1918, both of which featured naked women as the central figures. In the former, the female figure of peace was crucified on the sword and shield of Mars, above a pyramidal arrangement of dead and dying soldiers; the latter work depicted a victorious Australia under a representation of Britannia, also above a pyramid of lifeless bodies. The violent controversy that greeted the exhibition of these models prevented their development into full-size sculptures.

In Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914, Hoff employed his vitalist philosophy to show war “as a violent masculine attack” on the feminine force of “Peace/Civilisation”. Had it been used, this sculpture would have introduced a strong anti-war message in place of Dellit’s more conventional image of endurance, courage and sacrifice. Similarly, in his Victory after Sacrifice 1918, the naked woman is positioned in a manner reminiscent of crucifixion.

Through these works, Hoff expressed his thoughts about the absolutely destructive nature of war overcoming the life force. Leading church figures found Hoff’s expression of these ideas blasphemous. One called Crucifixion of Civilisation 1914 “a travesty of redemption gravely offensive to ordinary Christian decency”; another found the use of a nude woman to represent civilisation insulting to “devoted wives, mothers and sisters” and thought that the crucifix itself was the most inappropriate symbol for the sculptures. Architect and designer Florence Taylor hated the brutal realism of the dead and dying figures at the bases of the sculptures and also thought “a nude, rude woman” totally unconnected with warfare and unsuitable for a soldiers’ memorial. Other artists seemed to be the only people willing to defend Hoff’s symbolism. The debate about the artist’s right to express his personal beliefs in a public memorial was only resolved to the satisfaction of the Establishment when these controversial sculptures were never built.

MODIFICATIONS TO THE DESIGN

From the £75,000 available to construct the Memorial, Dellit estimated that it would cost £51,000 for the building and £23,000 for the sculpture, a total expenditure slightly less than the sum thought to be available. However, owing to the decline in the value of state and Commonwealth bonds during the Great Depression, the finance for the building had fallen to £68,700 by the time the investments were recalled. Attempts to reduce costs delayed the project, but the lowest sum agreed for the building alone was £55,050 (after changes to the exterior walls surfaces and the composition of the doors). This left barely enough in the fund to pay the architect and sculptor; nevertheless, the contract was signed in February 1932 and the work received Council approval the following month. Construction commenced soon afterwards as the Depression reached its worst point.

It was a reflection of the Memorial’s importance to the public that on 19 July over 15,000 people assembled to witness the official dedication of its two foundation stones by the Governor (“A Soldier”) and the Premier of New South Wales (“A Citizen”).

Originally, Dellit wanted the Memorial built of sandstone or synthetic granite on an 18-inch base of Bowral trachyte, a stone that was also to be used for the steps, landing and terraces. He went to considerable trouble to protect the sandstone from fretting by ensuring that it was all in direct light, and provided for copper flashing and secret gutters at the ziggurat-shaped top in an attempt to keep out any rainwater. However, the building was actually constructed in red granite from quarries near Bathurst; the podium and semi-circular stairs were faced in granite; and the terrace was formed in terrazzo.

In 1932 the RSSILA persuaded the Trustees to accept three stones from battlefields in Gallipoli, France and Palestine for inclusion in the Anzac Memorial, and the following year Dellit conceived a plan to incorporate them into the floors of the niches in the Hall of Memory. A fourth stone was procured from New Guinea, and all were set into surrounds of coloured marble in the form of the AIF “rising sun”. The names of major battles at each of these sites were added to the niche walls.

Approved in principle on 18 May 1933, the dome of stars was also a late inclusion in the Memorial. This feature began as a fundraiser, at a time when the project had lost support through the fracas over Hoff’s exterior statues. To cover the shortfall in funding the Memorial, the RSSILA offered stars for sale at two shillings each. In all, 120,000 stars were fixed to the ceiling, with each star representing “one who served”.

Various materials were suggested for the stars, such as precast cement covered by gold leaf, glass, and “composition”. Finally, in order to facilitate their attachment to the plaster ceiling, they were fashioned from plaster of Paris then gilded.

In another late change, the interior walls were lined in unpolished marble, while polished marble covered the floors. All doors were originally to be bronze, but funding shortages caused that specification to be changed to maple, studded with bronze nails. Dellit intended that each of the great amber windows would bear a different design for the different armed forces and auxiliary services. However, the building subcommittee asked him to collaborate with Hoff for an alternative that would better suit the sculptures. In April 1934 the new design, which combined the AIF symbol with a pattern of eternal flames, was etched on all the windows.

Dellit’s estimates for the cost of construction included allowances for non-structural details, such as the inscriptions he intended to have carved into the fabric of the building. He also envisaged the production of elaborate volumes recording the names of all who served that would be stored in the Archives Room in the Hall of Memory.

Above the archives’ doorway he provided a carving of the rising sun “borne aloft on the wings of time, together with the flaming sword of sacrifice, which points portentously to the years 1914–18”. Obviously, this feature of the Memorial was very important to Dellit, but, although he spent considerable time devising a system that would allow visitors to consult these books without damaging them, no special volumes were ever made to hold the names of New South Wales servicemen and servicewomen. Instead, the returned soldiers’ associations kept copies of the Anzac Memorial books printed during the war and used them for their records. Other items Dellit planned for the Archives Room were a set of the Australian Official War History and three panels bearing painted murals entitled “Britain and her Dominions Facing the Storm, 1914–1918”. Other paintings proposed for the stairs opposite the Archives room were “Heroism”, “The Departure” and “The Return”, but none was ever completed.

Dellit always intended that the space used for office accommodation at the base of the building should, when the need for that original use had passed, be incorporated into the Memorial. In the meantime, the spaces were allocated in such a manner that the RSSILA occupied the area on the southern side of the Hall of Silence and the TB and Limbless Soldiers’ Associations shared the area on its northern side. On the eastern side, Dellit added an Assembly Hall to balance the entry foyer on the west. The offices featured joinery in silky oak and parquetry floors of red mahogany. Light fittings in the shape of stars echoed the dome in the Hall of Memory.

Consideration of Hoff’s controversial exterior bronze sculptures had been deferred in November 1931, and the Trustees requested that Hoff reduce his progress payment. He angrily refused to do so, but accepted a compromise so that the work could continue. When the dispute became public in May 1932, the Trustees supported Hoff, even through the boycott that the Catholic Coadjutor, Archbishop Dr Michael Sheehan, imposed on the foundation stone laying ceremony. They believed Sheehan would later see that his opinion was “based on misconceptions” because they were using the same ceremony as the one that had opened the Cenotaph. The offending sculptures remained in limbo until 1933, when Dellit suggested a public appeal to finance their completion. By then, however, the Trustees were not willing to pursue the matter. Hoff refused to compromise his designs when the possibility of making them was raised again in 1934. Although these sculptures did have significant support, the outcry against them seems to have been responsible for discouraging further contributions towards the Memorial that year. A final attempt to raise £16,000 for its completion met with some refusals specifically directed at the nudity displayed in the proposed sculptures. This appeal only raised £9,310. The last time the Trustees attempted to complete the sculptures was in 1938, shortly after Hoff’s untimely death, but this proposal also failed.

The inscriptions that Dellit intended for the Memorial were the next casualties of the design. Foundation stones laid by Sir Philip Game and Premier Bertram Stevens on 19 July 1932 bear the words “A soldier set this stone” and “A citizen set this stone”, to indicate the contributions both soldiers and citizens had made to the building. However, these words were among the few that were actually transferred from concept to reality, even though Dellit believed that all his inscriptions were essential:

The object of a Memorial … should be to make its message not only as beautiful as possible but as clear and comprehensive as possible also: while beautiful form in architecture and sculpture and colour in mural decoration will always attract attention, there is no power like that of the written word to bring home vividly and permanently to those who gaze upon such works their meaning and inspiration.

Dellit supported Hoff’s proposal that the words “They gave Sons, Husbands and Lovers that the Race might Live” be inscribed in the base of the sculpture Sacrifice. But the bronzing was accidentally completed without any words, the only inscription being that set in the floor at the western entrance to the Hall of Silence: “Let Silent Contemplation be Your Offering”. As his competition entry had demonstrated, Dellit envisaged inscriptions above the doors to the Hall of Memory and the niches in that space near the Well of Contemplation. Below, in the Hall of Silence, he wanted a list of the major battles; he also suggested that the figures on the buttresses outside should also be identified in words. Doubtful about the value of these ideas, the Trustees agreed only to the list of battle areas in the Hall of Silence and delayed a decision about the other inscriptions. Initially, they consulted the poet and returned soldier Leon Gellert, then left the question with Professor Samuel Hook, who himself consulted Professor of Modern Literature Sir Mungo MacCallum, Fisher Librarian H.M. Green and war correspondent and historian Charles Bean.

These experts ruled against the numerous labels that Dellit had suggested:

In our opinion the effect would be to disperse rather than concentrate interest. We think three inscriptions would be quite sufficient – the two outside of the Memorial and one around the Well of Contemplation.

The short time remaining until the scheduled dedication by the Duke of Gloucester prevented the Trustees from canvassing any more opinions. To mark the dedication of the building, they chose one of two simple statements submitted by Hook, Green and Bean: ‘This Memorial was opened by a son of the King on 24th November 1934’. This matched the democratic sentiment expressed in the foundation tablets laid by “A Soldier” and “A Citizen”, and reinforced the suggestion that the Memorial was “of and for the people”. Whether through procrastination, or by policy, Dellit’s interpretive messages were ignored.

BUILDERS AND CONTRACTORS

The Trustees Building Committee comprised L.A. Robb, RSSILA President; G.M. Farrow, President of the Limbless Soldiers’ Association; E.J. Payne, the Public Trustee; H. Armitage, Deputy Governor of the Commonwealth Bank; Professor A.S. Hook; and J. Stagg, the Trustees’ Honorary Secretary; W.C. Cridland of the TB Soldiers’ Association joined in 1932, and R.D. Hadfield later replaced Stagg as Secretary.

The Trustees specified that the Memorial must be built of Australian materials and by Australian workmen. The Sydney building firm Kell and Rigby won the tender for the construction of the Memorial. It was encouraged to give preference to returned servicemen and applied to the RSSILA Labour Bureau for the use of their workers on the project. Finding suitable work for returned soldiers had been an important service provided by the RSSILA since the first years of peace, but the urgency became even greater during the Great Depression. Unemployment had begun to increase in the late 1920s as Australia’s short-lived postwar boom came to an end. Even though the worst of the Depression was said to be over by 1934, many people were unable to obtain work until the outbreak of the Second World War. It then became apparent that many returned soldiers had been out of work from the time that they had returned from the First World War. Their difficulties were revealed in the large number seeking positions in the Garrison Force created to protect the home front and in the large number who enlisted for a second experience of service overseas.

Working on the Anzac Memorial with Kell and Rigby were numerous sub-contractors. These professionals and artisans included structural engineers R.S. Morris & Co Ltd; stone masons Melocco Bros Ltd, who carved the wreath around the Well of Contemplation; Messrs Loveridge and Hudson Ltd, who prepared the granite facing on the outside walls; J.C. Goodwin and Co Ltd, who supplied the amber glass; Art Glass Ltd, who completed the sandblasting; and T. Grounds and Sons, who manufactured the stone figures on the buttresses and the funerary urns to Hoff’s design. The London firm of Morris Singer & Co Ltd cast the central sculpture and bronze panels over the doors, but the flame surrounding the sculpture and the bronze grilles on the lower windows were made in Australia by Castle Bros; Kell and Rigby produced the bronze nails studding the doors. Homebush Ceiling Works made the ceilings and supplied the 120,000 stars for the dome, the latter being gilded by A. Zimmerman, while Kellor and Yates completed the plasterwork. The Electrical and General Installation Co was responsible for the electrical work, and Nielsen and Moller made the light fixtures. Later Dellit was able to persuade the City Council to supply temporary floodlighting for the building, a service made permanent in 1938.

THE OPENING CEREMONY

The crowds attending the official opening of the Anzac Memorial on 24 November 1934 were estimated at 100,000 – It was a simple ceremony; in keeping with the words on the foundation tablets, it aimed to show that the building was of and for the people.

The official party assembled on the western terrace and the people crowded around the Memorial, and in all the buildings that overlooked it. Prince Henry, the Duke of Gloucester, made the dedication speech, and the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney, Dr Howard Mowll, gave the prayer.

'To the Glory of God, and as a lasting monument of all the members of the Australian Forces of the State of New South Wales, who served their King and country in the Great War, and especially in grateful remembrance of those who laid down their lives, we dedicate this Anzac Memorial'.

The message was for those who returned as well as those who died, although some saw it more as a monument to those who did not return.

Catholic Archbishop Sheehan boycotted this event on the grounds that it was 'not entirely Catholic in character'.