This wooden hinged ditty box is currently on display in the Navy section of the Anzac Memorial’s permanent exhibition. It belonged to 103 Able Seaman William John Lane during the Great War. Ditty boxes have long been used by seamen and fishermen for storing small personal possessions such as pens, tobacco pipes and cutlery whilst at sea. It is quite possible that Lane personalised the lid of the box himself by carving onto it his name, company and hometown identification.

But what was the significance to Lane of ‘Herbertshohe, New Britain’ and the date 11 September 1914?

William Lane was born in Newtown, Sydney on 14 February 1894. He later trained as a boilermaker’s apprentice and shortly after his seventeenth birthday in March 1911, Lane joined the Naval Cadet Service. On 1 July 1912, he transferred to the Citizen Naval Force as a stoker, second class. Perhaps, with his trade qualifying him for loftier engine room duties, two years later he was promoted to stoker. And when the Great War broke out, William Lane was one of the first Australians to volunteer for military service overseas.

THE OUTBREAK OF THE GREAT WAR

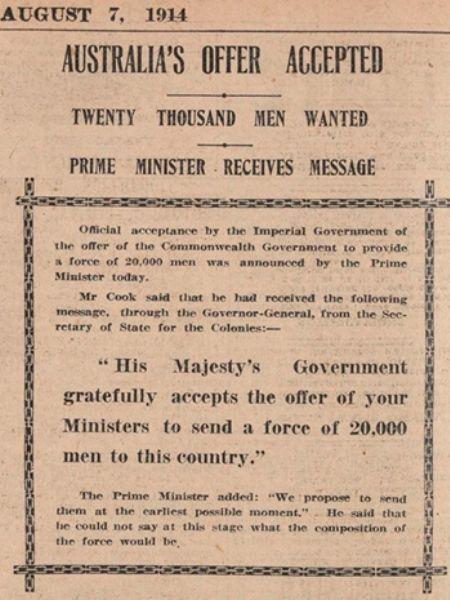

Great Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 4 August 1914 (10am on 5 August, Eastern Australian Time) was greeted in Australia, as it was across the British Empire, with great fervor and enthusiasm. As proud and loyal British subjects many Australians saw the war in Europe ‘as our war too’ and in the first few weeks the rush to enlist was overwhelming. Yet Australia’s promise to stand by Britain ‘to our last man and our last shilling’ meant that new armed forces had to be created because the existing Australian Commonwealth Military Forces could not leave Australia and its territories. These forces had been established as home front defensive forces, not expeditionary Imperial ones. And so, an all-volunteer force of 20,000 men for overseas deployment was initially raised; its founder, Scottish born Brigadier-General William Throsby Bridges called it the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).[1] According to Bridges he wanted a name ‘that will sound well when they call it by our initials.’[2] On 6 August, London cabled its acceptance of the force and asked that it be sent as soon as possible.[3]

Nationally, between 1914 and 1918, 412,953 men enlisted in the AIF. Of these 331,781 embarked for service overseas. In total 164,000 men from NSW volunteered and just over 130,000 served overseas.[4] Additionally, over 8,000 men served with the recently established Royal Australian Navy (RAN) which spent most of the war under the control of the British Admiralty; throughout the conflict Australian sailors and ships were sent where Britain needed them most.[5] The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) was also created as an entirely separate force. It was announced on 10 August 1914 as a ‘small mixed naval and military force for service within or without Australia.’ Rather than a long-term overseas deployment to Europe however, its task was to be a much more immediate one with orders from the British to ‘neutralise’ German New Guinea and remove a hostile power from the Pacific region.[6] Out of 3,651 enlistments to this joint army-navy contingent 3,011 saw action with the AN&MEF.[7]

AUSTRALIA'S FIRST ACTION

Just two weeks after Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, on the afternoon of Tuesday 18 August 1914, the streets of Sydney and the city’s harbour foreshore were thronged with tens of thousands of enthusiastic well-wishers as men of the AN&MEF marched through the city en route to Fort Macquarie.[8] Here, they boarded ferry steamers to be taken over to Cockatoo Island. Since 1913 the large working Sydney harbour island had been the official dockyard of the RAN. Young William Lane was amongst them and upon arriving at the island, he embarked aboard HMAT Berrima as a member of 3 Company, Royal Australian Naval Reserve, AN&MEF.

Prior to the war, HMAS Berrima had been a P&O Company cruise liner plying the lucrative London, Cape Town, Sydney passenger route. In August 1914, HMAS Berrima was requisitioned by the RAN and was quickly converted into an armed merchant carrier and troopship. Shortly after 7am on 19 August 1914, HMAT Berrima departed from Cockatoo Island carrying 500 men of the AN&MEF and a hastily recruited battalion of 1,000 infantry troops from NSW. Under the command of militia officer Colonel William Holmes, who had been awarded a DSO during the Boer War, the AN&MEF was heading off towards Australia’s first military action of the Great War.[9] Six companies of the Australian naval reserve, under the command of Joseph Arthur Hamilton Beresford, would follow soon after.[10]

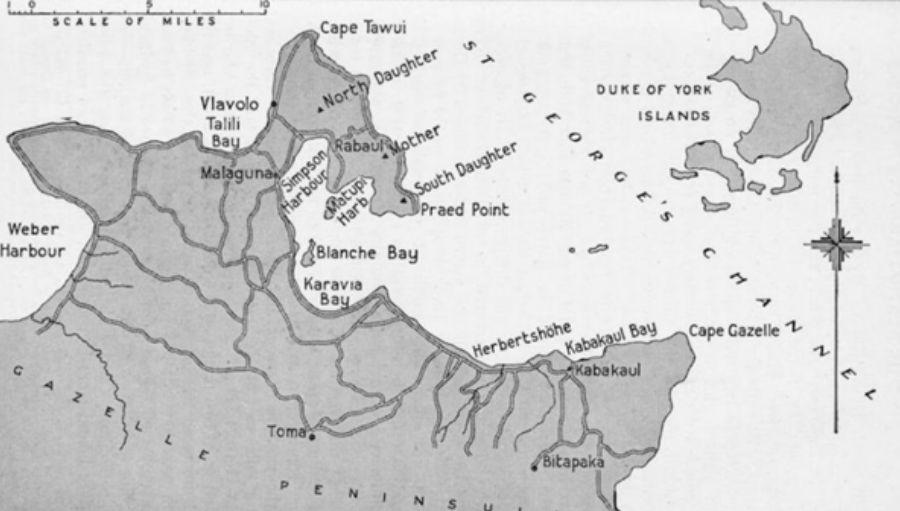

The AN&MEF initially sailed for Port Moresby, via Palm Island to the north of Townsville in Queensland. On 7 September the expeditionary force departed for Rabaul on the largest and most important of the islands in the Bismarck Archipelago – the New Guinean island of New Britain.[11] At dawn on 11 September, small parties of troops landed south east of Rabaul at Kabakaul on the shore of Blanche Bay. Others landed at nearby Herbertshohe. Their target was the inland wireless station at the village of Bitapaka which was being used to send vital intelligence signals to Vice Admiral von Spee’s German East Asiatic Squadron of the Imperial German Navy. Despite a series of skirmishes with German colonial troops and local Melanesian auxiliaries along the mined and thickly forested jungle tracks to Bitapaka, by 7pm the enemy radio station had been secured. It was certainly a victory of sorts, although unfortunately, the operation was marred by seven AN&MEF fatalities.[12] These men were the first of more than 60,000 Australians killed during the Great War. One German and thirty Melanesians had also died in their efforts to defend the wireless station.[13]

Ten days later, on 21 September the rest of the island ceded and the British flag was raised. An official surrender agreed to by Ernst Haber, the acting Governor-General of German New Guinea saw German officers and their local troops lay down their arms. The conditions of the surrender proposed by Colonel William Holmes required that all German civilians take an oath of neutrality.[14] And a proclamation read at the surrender firmly told the native New Guineans what the new realities were; ‘All boys belongina one place, you savvy big master he come now, he new feller master, he strong feller too much … No more Um Kaiser, God save Um King.’[15] The rest of the Pacific campaign witnessed a speedy German capitulation and by December the AN&MEF had occupied and garrisoned the remaining enemy possessions in the territory.[16]

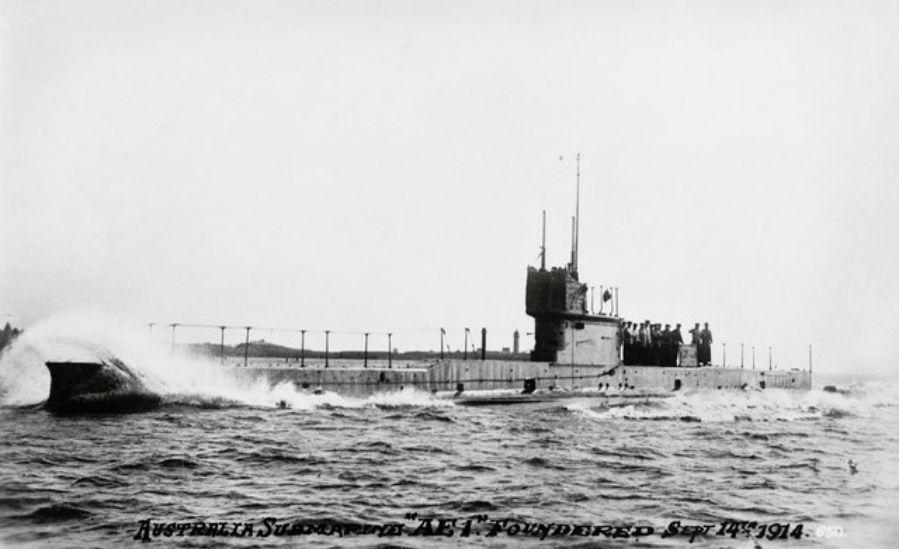

According to historian Robert Stevenson, ‘New Guinea was Australia’s most successful campaign of the Great War.’[17] Yet it was also darkened by a profound tragedy with the first significant loss for the RAN. On 14 September 1914, the Australian submarine HMAS AE1, commanded by Captain Thomas Besant disappeared in the waters off Rabaul whilst out on patrol. All 35 officers and men were lost and the wreck remained undiscovered for 103 years until it was eventually found off the Duke of York Islands in 2017.

Able Seaman William Lane participated in the landing at Herbertshohe and the subsequent capture of the Bitapaka wireless station on 11 September 1914. Today, we can only wonder how the young twenty-year-old from Sydney felt about his first military encounter, although the carving on his ditty box perhaps indicates the personal significance of the place and date to him as a raw young recruit. Lane remained stationed at Herbertshohe until February 1915 after which he returned to Sydney. For the remainder of the war he worked where his military service had first begun - on Cockatoo Island.[18] And by 1 June 1917, William Lane had been promoted to head stoker.

Today, the Rabaul Commonwealth War Cemetery stands on the site of the Bitapaka wireless station where the first Australians killed during the war were buried. A soil sample from the location features in the Anzac Memorial’s Hall of Service. Upstairs, in the Hall of Memory, Kabakaul is etched into a niche in the wall to commemorate the landing place of those intrepid, valiant volunteers who served and died in Australia’s first battle of the Great War.

Lest we forget.

Article by Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The son of an English naval officer, Bridges died at Gallipoli in May 1915 and was one of only two soldiers who died in the Great War who was later brought home. The other was the ‘Unknown Soldier’, disinterred from a French cemetery in 1993 and laid to rest at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

[2] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Volume One, The Story of Anzac from the outbreak of war to the end of the first phase of the Gallipoli Campaign, May 4, 1915, 11th edition, 1941, p 36.

[3] A. K. Macdougall, Australians at War; A Pictorial History, Five Mile Press, Victoria, 2002, p 30.

[4] Approximately 550 servicemen were Aboriginal.

[5] The Royal Australian Navy was established in 1911.

[6] ‘In Australia’ Argus (Melbourne), 10 August 1914, p 8. At its closest point to mainland Australia, New Guinea is less than 100 miles (160 km) away; the proximity of enemy German possessions in the Pacific were thus of specific concern and their capture deemed vital to preserving the security of Britain’s Commonwealth ally in the southern hemisphere.

[7] Brad Manera, New South Wales and the Great War 1914 to 1918, State of NSW, 2011, p 8. Men signed up for six months with the AN&MEF rather than for the duration of the war as was usual with the AIF.

[8] Today Fort Macquarie is the site of the Sydney Opera House at East Circular Quay, Bennelong Point.

[9] Holmes was a citizen soldier whose civilian work was as secretary of the Sydney Water and Sewerage Board and whose father had first come to Australia in the 1840s as a member of the 11th Foot.

[10] Thomas Kenneally, Australians; From Eureka to the Diggers, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2011, p 294.

[11] Between 1884 and 1914 New Britain was known as New Pomerania and it was part of German New Guinea. Historian John Connor refers to it as ‘Neu Pommern.’

[12] Five other Australians had been wounded by enemy sniper fire.

[13] Chris Coulthard-Clarke, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2001, p 97.

[14] With the German surrender, Holmes became the military administrator of the captured territory, a position he retained until 8 January 1915.

[15] Cited in Thomas Kenneally, Australians; From Eureka to the Diggers, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2011, p 296.

[16] New Ireland, the Admiralties, Bougainville and the German Solomons were all subsequently occupied by small forces despatched by Colonel William Holmes.

[17] Robert Stevenson, The War with Germany; The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War, Volume 3, Oxford University Press, 2015, p 206. In March 1915, the AN&MEF was disbanded having served its six months and almost three quarters of its members immediately re-enlisted with the AIF. In New Guinea the AN&MEF was replaced by battalions of the Tropical Force. The Australian military occupation of New Guinea lasted until 1921 when the League of Nations handed the islands over to Australia and a new civilian administration took over.

[18] During the war, the dockyard facilities on Cockatoo Island were greatly expanded to accommodate the nearly 2000 ships which docked there between 1914 and 1918. By 1919, the workforce on the harbour island was more than 4000.