In 2021 the Anzac Memorial was fortunate to acquire this medal trio comprising the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal 1914-19, together with a Mothers and Widows Ribbon with one star. After the Great War, they were sent to Louisa Turner to commemorate the wartime service and sacrifice of her husband 655 Private Alfred Turner who lost his life on Hill 60 at Gallipoli in August 1915.

Alfred James Turner was born in Battersea, in South West London in 1881. It is unclear from the historical records when or why he emigrated to Australia. In 1915, thirty-four-year-old Turner was working as a storeman for W.D. & H.O. Wells Australia Limited, a large tobacco manufacturing company, whose headquarters were on Castlereagh Street in Sydney. On 5 February 1915, Turner enlisted with the AIF leaving behind his wife Louisa and twenty-one-month-old daughter Nancy Lillian at home in Marrickville.[1] He was subsequently posted to the 18th Battalion which was raised at Liverpool in New South Wales in March 1915 as part of the 5th Brigade of the Australian 2nd Division. Like Turner, most of the 1004 volunteer enlistees of the full-strength battalion were from the Sydney region. On 25 June 1915, under the command of Boer War veteran Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Earnest Chapman VD, the men of the 18th embarked for Egypt per HMAT Ceramic A40.[2] Here they underwent further albeit limited military training until mid-August.[3] On the night of 19 August, the battalion landed at Anzac Cove, having been committed to the final operation of the August offensive to break the deadlock on the Gallipoli Peninsula – the attack on Hill 60.

THE BATTLE FOR HILL 60

‘For connoisseurs of military futility, valour, incompetence and determination, the attacks on Hill 60 are in a class of their own.’ [4]

Kaiajik Aghala (Hill 60) is a long low rise 60 feet high between the then established beach-head at Anzac Cove to the south and the British forces at Suvla Bay, further north. The plan to take the Turkish trenches on the top of the hill would have widened and strengthened the corridor of foreshore and secured a vital link between the two allied positions.[5] Yet poor aerial reconnaissance and inadequate maps of the territory, together with very determined local resistance meant that ultimately, the operation was to become another tragedy of the Dardanelles Campaign. An initial attack was made on the ‘brilliant and hot’ afternoon of 21 August by a mixed force of British, Indian, New Zealand and Australian troops, including men of the 13th and 14th Battalions.[6] But with the enemy occupying the advantageous high ground they were viciously cut down by machine gun and artillery fire on the lower slopes of the hill. Of the 150 Australians from the 13th Battalion in the first wave, 110 were killed or wounded at once and others were hit shortly afterwards. The 14th Battalion which manned the second wave suffered the same fate.[7] With the dense prickly scrub on the sloping terrain another challenging obstacle, the wild landscape further conspired against them when ‘the scrub caught fire. Wounded men were roasted; others died when their ammunition pockets exploded.’[8] By nightfall, with the dreadful aftermath of the slaughter visible to all, and mangled bodies left where they had fallen, the attackers had merely gained a slender foothold on Hill 60. It had been a complete military debacle - yet it was clear to those in high command that fresh reinforcements were required to buttress the flagging fortunes of the by now battle-weary troops, many of whom had been at Gallipoli since 25 April 1915. And so, the recently arrived 18th battalion, consisting of men who Charles Bean later recalled ‘came to the tired and somewhat haggard garrison of Anzac like a fresh breeze from the Australian bush’ were called upon to continue to fight for the hill.[9] Despite the promise of their additional strength, the 18th were raw, mostly young recruits; full of courage, but completely lacking in military experience.

At dawn on 22 August, the NSW raised 5th Brigade led by the 18th Battalion renewed the attack. The troops were woefully equipped and had been ordered to fight only with bomb and bayonet. Unfortunately for the 18th the availability of bombs was few and far between, and so the charge was largely characterised by savage, desperate hand to hand fighting with the barbarous bayonet alone. Bravely, they stormed the Turkish trenches 750 strong; within a few hours they had lost 372 men and 11 officers of whom half had been killed.[10] By all accounts it was an unmitigated disaster and by the end of the day, ‘Hill 60 was still unconquered and a new battalion had been ruined.’[11]

IN THE THICK OF IT

We can only wonder what Alfred Turner made of the ‘hastily conceived and poorly arranged attack’ with its resulting bloody carnage.[12] Perhaps he regretted his decision to enlist. Or, as a British born subject, was it his patriotic duty to serve his King and Commonwealth? Maybe he was thinking of his wife and young daughter half a world away. Or was he simply, right now, in a desperate fight to preserve his own life? His comrade in arms, 228 Private James ‘Jimmy’ Turnbull Grieve, a twenty-one-year-old farm labourer from Kellyville in NSW had enlisted on 16 February 1915 and also arrived at Gallipoli with the 18th. Grieve wrote home to his parents on the morning of 27 August and vividly related his battalion’s first engagement on Hill 60;

It was awful to hear the moans and groans of the wounded and the dying. One poor chap lying a few feet away from me was wounded in the knee. I bandaged it up for him as well as possible and he started to crawl back but I heard after that he was shot dead while crawling back poor fellow. There were bullets and machine guns whizzing all around, also shrapnel which is worst of all. It fell all around me and several chaps fell around me and yet I escaped. It was marvellous how I came out without a scratch, but I expect it was my luck.[13]

4PM, 27 AUGUST 1915

The assault was resumed just a few hours after Grieve had composed his letter, on the afternoon of 27 August with the attacking force cobbled together from the remnants of nine different Australian and New Zealand battalions. For the next three days both sides pelted each other with bombs and inflicted pitiless ferocity against their enemy. As a result, the Turkish trenches on the hill were ‘taken, partly lost, and re-taken again.’[14] Yet unable to go any further and with the surviving allied troops sick, demoralised and utterly exhausted, the battle for Hill 60 ended in stalemate. By its close, there were almost 2,500 British and colonial casualties; and more than half the 18th Battalion from New South Wales were dead, wounded or missing in action.[15]

Young Jimmy Grieve never got the chance to post that letter home to his parents in Kellyville. It was later found left abandoned in a dugout near Hill 60 and was souvenired for safekeeping. Following the attack of 27 August, Grieve was reported as missing in action and, unlike his letter which he had ended with a row of fifteen kisses, his body was never recovered. His luck, as for so many others, had wretchedly run out. Alfred Turner also disappeared on that day of the second battle for Hill 60. Louisa Turner, like many wives and mothers waiting for news back home, and anxiously reading the casualty lists reported in the daily newspapers, was eventually informed in October 1915 that her husband was now missing.

MISSING IN ACTION

During the Great War, soldiers reported missing in action were often the subject of a later official examination.[16] Five months after the final offensive on the Gallipoli Peninsular, a military court of inquiry was held at the AIF training camp at Tel el Kebir on the edge of the Egyptian desert. The investigation was convened to hear eye witness accounts concerning the men who had vanished on Hill 60. On 21 January 1916, those assembled heard conflicting reports regarding Alfred Turner’s fate. One witness said he ‘remembered Turner’s casualty well’ and recalled that he had been killed by a shell in the trenches early in the afternoon of 27 August before the proper fighting commenced. Yet this witness also remembered him as a tall, thin man; Turner however only stood at 5 feet and 4 inches.[17] Another suggested he took part ‘in the charge on the left of Anzac’ on 28 August ‘and was never seen again’. A third witness stated that Turner had been acting as a stretcher bearer during the second attack prior to his disappearance. It was all rather uncertain. But whatever had happened to Alfred Turner on or after 27 August 1915, the inquiry determined that it was now ‘reasonable to suppose he was dead.’ On the same day, following evidence that a bullet had felled him and he was left for dead, the inquiry came to the same gloomy yet inevitable conclusion with regards to Jimmy Grieve.

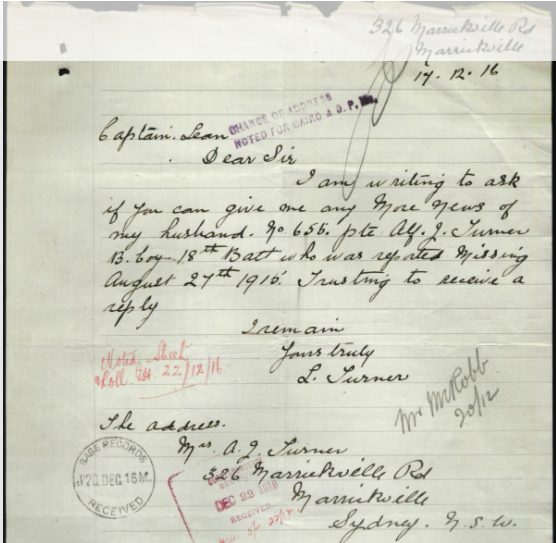

ANXIOUSLY WAITING FOR NEWS

In December 1916 Louisa Turner sent a hand-written letter to AIF base records headquarters in Melbourne asking if any further information about her husband had come to light. It had now been over a year since she had first heard that Alfred was reported missing in action.[18] Yet Turner’s death was not ratified in the Australian casualty lists until March 1917. In July 1917, his widow sent another letter inquiring if any personal effects belonging to her husband might be returned to her. The reply was a rather terse one; there were to date no personal effects to be sent back to her. Further letters from Louisa and her brother-in-law Charles Turner wondering if Alfred’s body had ever been recovered or a gravesite identified were responded to in a similarly brusque manner; quite simply Alfred James Turner’s final resting place was unknown. And so it was to remain. Today his mortal remains probably still lie where he fell, and his service and sacrifice are commemorated on Panel Number 63 at the Lone Pine Memorial alongside almost 5,000 other Australian and New Zealand servicemen who were lost forever in the waters and soil around Gallipoli in 1915. James ‘Jimmy’ Grieve is honoured on Panel Number 61 at the same memorial.

IN MEMORY OF THE FALLEN

In addition to Turner’s three war medals, Louisa Turner received a Memorial Scroll and King’s Message in August 1921 and a Memorial Plaque in June 1922 for her late husband’s service. For her own sacrifice, she also received a Mothers and Widows Ribbon with one star.[19] Whilst we do not know the subsequent fate of the plaque and scroll, Turner’s medals and Louisa’s ribbon are a very valuable acquisition for the Anzac Memorial. They are a poignant reminder of the Battle of Hill 60 and the role played by the NSW raised 18th Battalion. These small yet significant tokens also complement the Memorial Plaque in our collection that was sent to Tilly Odell, the younger sister of 1012 Private Charles Henry ‘Bluey’ Woodlock, 18th Battalion, AIF. Like Turner and Grieve, Woodlock went missing in action on 27 August 1915. Tragically, for his siblings waiting patiently for news from the front, his death was not confirmed by an official military inquiry for another two years after his disappearance.[20]

REMEMBERING HILL 60

Today Hill 60 is remembered in the same named lookout above the spectacular coastal landscape at Port Kembla, Wollongong, NSW. During the Second World War a series of fortifications and concrete bunkers were built here to protect the vital industrial centre of the Illawarra region. At the Anzac Memorial, Hill 60 is a battle honour etched into the Hall of Memory and there is a soil sample from the tragic battle site in the Hall of Service.

Lest we forget.

Article by Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

[1] He also had an older brother, London born Charles William Witham Turner who was residing in East Sydney on the eve of the Great War.

[2] See https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showPerson?pid=50375

[3] In September 1915, Chapman resigned his commission in the AIF at Gallipoli. He was a month away from his 47th birthday and was suffering from shell shock and poor health.

[4] Robert Rhodes James, Gallipoli, Pimlico, London, 1999, p 309.

[5] Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, 2001, p 110.

[6] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 728.

[7] Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, first published 2001, reprinted 2002, p 484.

[8] Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, first published 2001, reprinted 2002, p 485. See also Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 735.

[9] Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 739.

[10] There were over 1300 British and colonial deaths by the end of the day. Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 744; Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, 2001, p 110; Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, first published 2001, reprinted 2002, p 485.

[11] Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, first published 2001, reprinted 2002, p 485.

[12] Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, 2001, p 110.

[13] Cited in Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, first published 2001, reprinted 2002, pp 485-86.

[14] Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, 2001, pp 110-11.

[15] For the rest of the Gallipoli campaign, the 18th played a purely defensive role, being primarily responsible for holding Courtney's Post. The remaining members of the battalion left Gallipoli on 20 December 1915. Their next decisive battle was at Pozieres on the Western Front during the European summer of 1916.

[16] During the Great War the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau also played a pivotal role in trying to ascertain the fate of so many lost men.

[17] According to his service record he weighed 138 pounds which at five feet and four inches would have arguably made him ‘slight’ rather than ‘thin’.

[18] Likewise, Jimmy Grieve’s mother Agnes had written to AIF base records headquarters in Melbourne in November 1916 asking for any further news of her still missing son and the possible return of his belongings.

[19] According to the Anzac Memorial’s Senior Curator and Historian, the Mothers and Widows Ribbon in this recent acquisition is one of the finest examples he has seen.

[20] There were two military inquiries made into Woodlock’s fate. The first, held at the village of Fricourt on the Somme in April 1917 ended with no verdict as ‘there was no evidence available in the battalion regarding this man.’ The second, convened at Rouen in Normandy on 3 September 1917 heard evidence that Woodlock had gone out with a bombing party and had been blown up in a sap on Hill 60 on or about 27 August 1915.